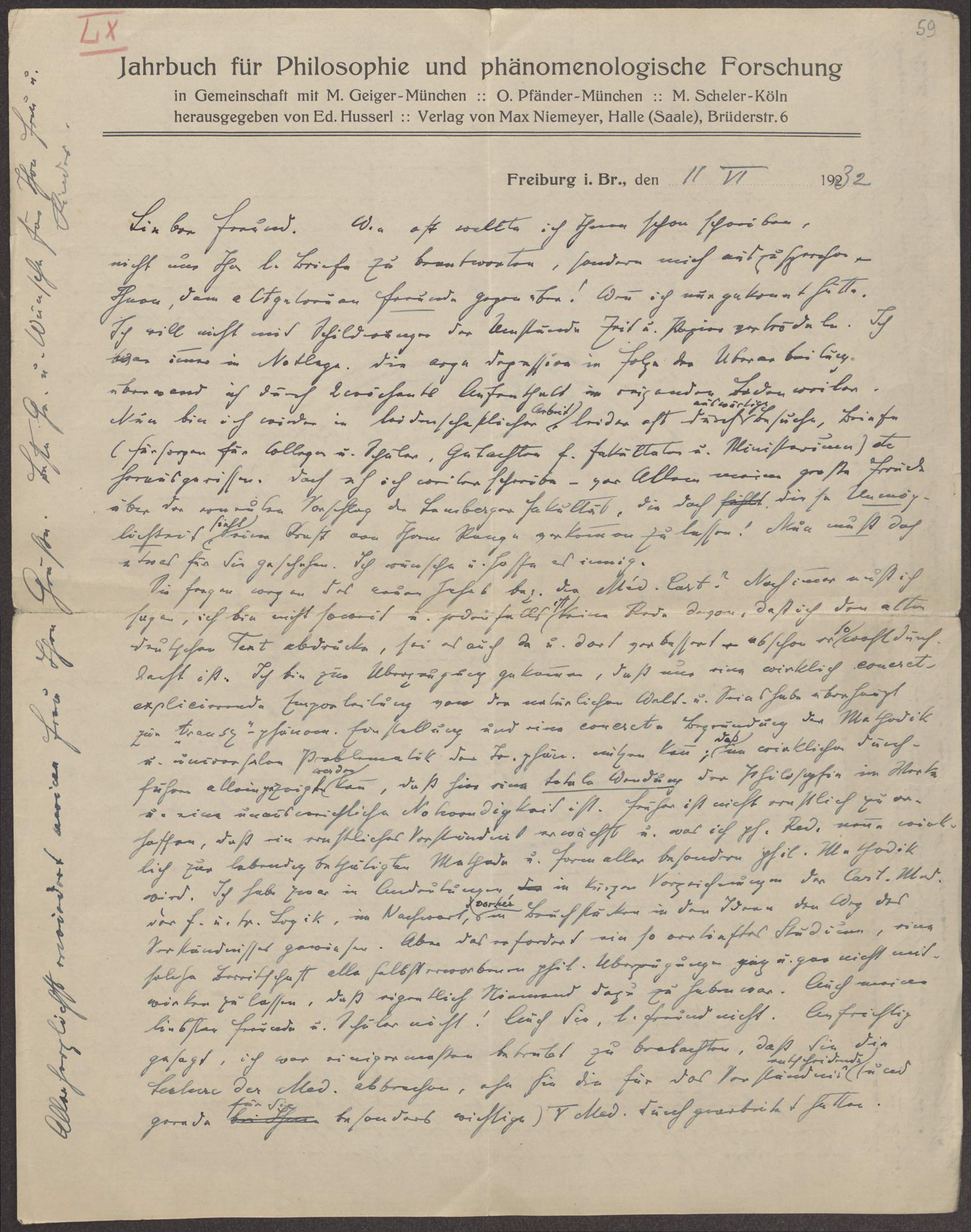

Letter from Edmund Husserl written 11.06.1932

Freiburg, 11.VI.1932

Dear Friend,

How many times have I wanted to write to you, not just to reply to your letters, but to tell you what’s on my mind – to express my thought to you, my faithful friend! If only I could. I do not want to waste time and paper talking about the specific circumstances. I was in a constant state of distress. I overcame my terrible depression that resulted from the revision of my work by staying in the lovely town of Badenweiler for two weeks. I am now back to working fervently; unfortunately, there are many distractions such as external visitors, letters (assisting colleagues and students, reports for faculties and ministry), etc. But before I go on, I would like to express my great joy at the renewed proposal of the faculty of Lwow, which recognizes the possibility of wasting a force of your caliber! I am sure something positive is finally going to happen for you. I truly hope so.

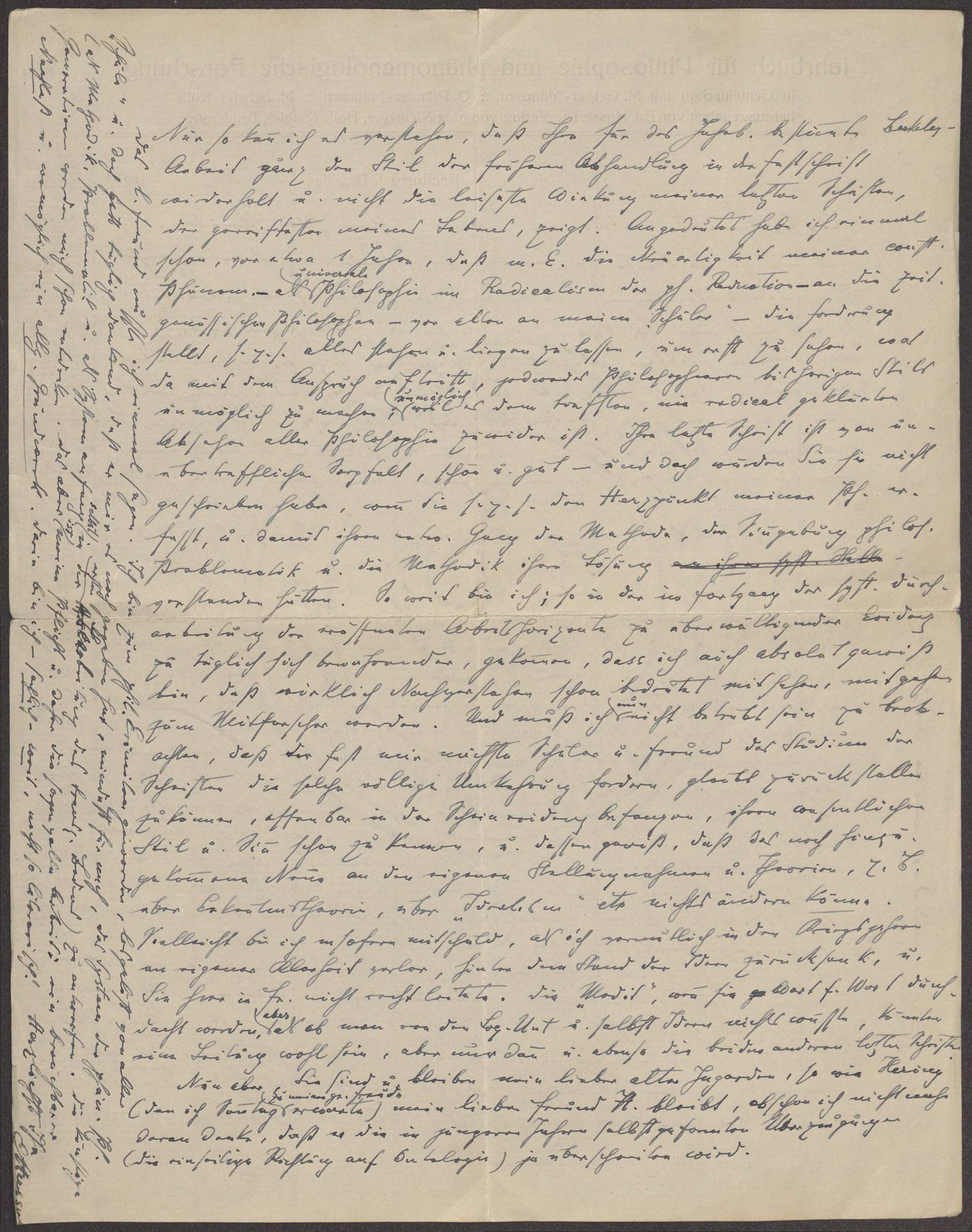

You asked about the latest Yearbook and the Méd[itations] Cart[ésiennes ]. I still have to say I am not ready, and in any case, there is no question that I would print the old German text, even if it has been edited here and there and although it has been precisely thought through. I have come to the conclusion that only a truly concrete explication that ascends from the natural possession of the world and of being to the “transc[endental]” phenom[enological] stance and a concrete justification of the methodology and universal problem of tr[anscendental] phen[omenology] can be useful; that in the actual practice alone it can be demonstrated that there is a total shift in philosophy and that it is an inevitable necessity. Otherwise, one cannot expect others to grow in understanding, and ensuring that my so-called ph[enomenological] red[uction] will become an alive and active methodology and form for all special philosophical methodology. Well, I briefly mentioned these insights in the Cart[esian] Med[itations] of the F[ormal] and Tr[anscendental] Logic, in the epilogue [Ideas I], and previously in fragments in Ideas. But this requires such deep study, a commitment and willingness to put aside all previously obtained philosophical convictions that nobody was interested in it, not even my dearest friends and students! Even you, my d[ear] friend, did not take advantage of this opportunity. Quite frankly, I was sad to realize that you stopped reading the Med[itations] before you worked through Med[itation] V, which is the key to understanding (and particularly important for you). This is the only explanation I have for your Berkeley work, which was to be included in the Yearbook and repeats the same style of the previous essay in the commemorative publication and does not show the slightest evidence of an effect my past works, the most mature ones of my life, may have had on you.66 I previously hinted, about one year ago, that in my opinion, the novelty of my const[itutive] phenom[enology] – as a universal philosophy in the radicalism of ph[enomenological] reduction – requires, particularly my “students”, to drop everything and investigate what it is that supposedly makes any philosophizing of a previous style impossible; impossible, because it goes against the deepest, never radically clarified purpose of all philosophy. Your last paper is of unsurpassable diligence, beautifully and well written – and yet you would not have written it if you had grasped the heart of my ph.* and therefore recognized the necessary method, the meaning of philosophical problems and the methodology leading to their solution. This is how far I have come; during the course of my syst[ematic] immersion in the work horizons that opened up to me, I have come to realize and found overwhelming evidence and therefore I am absolutely certain that actual empathetic following and understanding means seeing along, going along, and becoming a co-researcher. Should I not be saddened to observe that the student closest to me, who is also a friend, believes that he can postpone the study of those writings, which demand a complete turn in philosophy, because he is apparently biased by the illusory evidence that he already knows their essential style and meaning. Moreover, him being certain that the yet to be discovered new could not change any of his own opinions and theories regarding matters such as epistemology, “Idealism”, etc. Perhaps it is in part my fault, since I probably lost some of my own clarity during the years of war, hid behind the state of Ideas and failed to guide you properly while you were in Fr[eiburg].67 The Medit[ations], when thought through word by word as if one knew nothing about the Log[ical] Inv[estigations] and Ideas, could lead us the way, but only then; and the other two last writings too.

Well, you are and remain my dear old Ingarden, just as Hering (whom I am expecting on Sunday to my great joy) remains my dear friend H[ering], although I no longer think that he will ever exceed the beliefs he formed during his younger years (the one-sided fixation on ontology). This, my d[ear] friend, is something I had to tell you. I have become a philosophical hermit, detached from what is “commonly taught”, and I thank God daily that he has blessed me with it, at least for me, helping me design a system of phen[omenological] ph[ilosophy] (as methodology, set of problems, and as the beginning of a system in the first adaptation of the transc[endental] groundwork). I am confident that future generations will discover my work. This is my duty and therefore, the anxious work. A useful bequest and possibly a general foundation. Factually, I have come a long way, not so literary! Yours sincerely,

E. Husserl

My wife would like to reciprocate your kind regards. Please send our kind regards and best wishes to your wife and children.