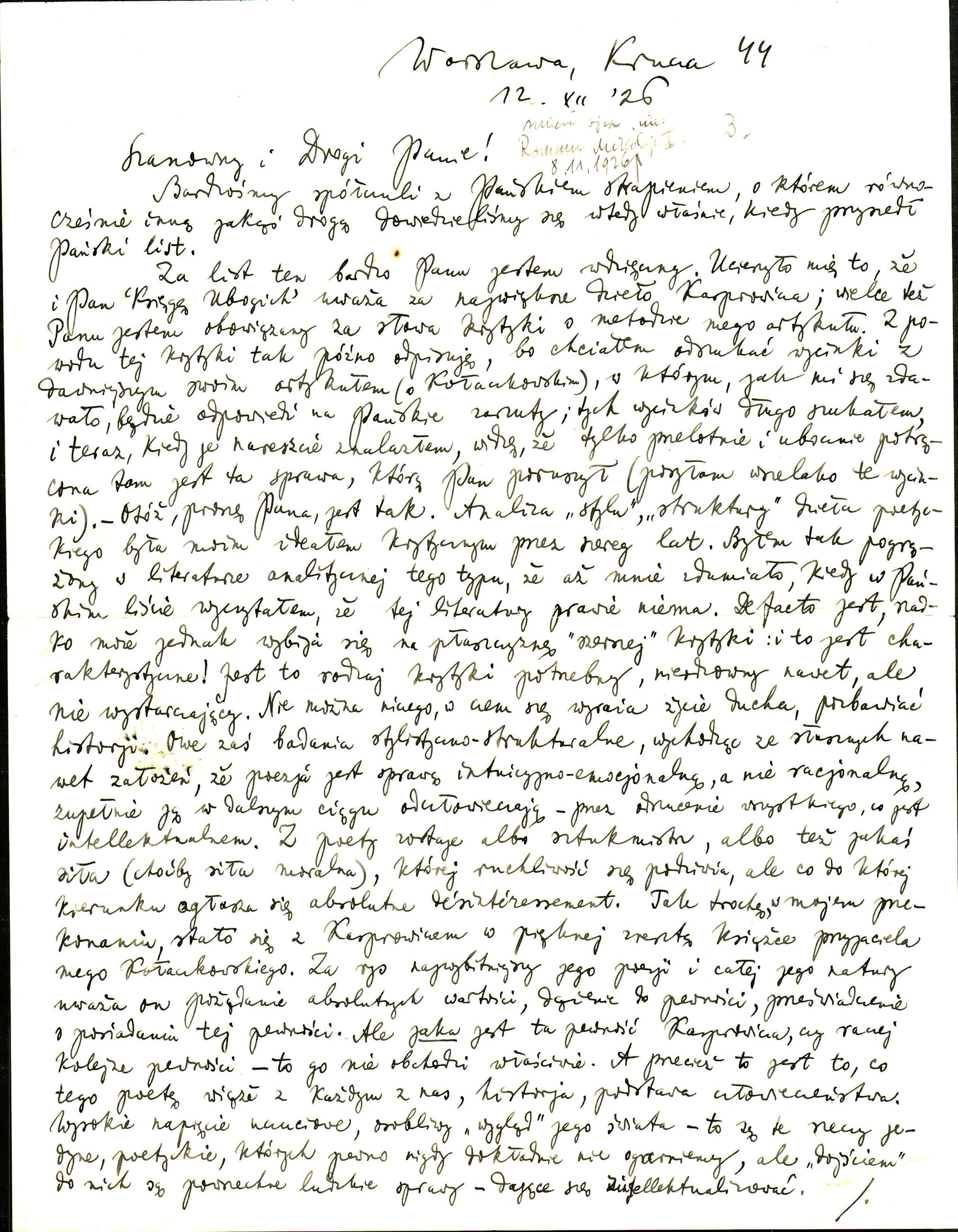

Letter from Wacław Borowy written 12.12.1926

n n n n n n n n Warsaw, Krucza St. 44

n n n n n n n n n 12.XII.’26

n Dear and Beloved Sir!

n We offer our most sincere sympathies to your distress, which we found out about at roughly the same time your letter arrived from some other source.

n I am very grateful for this letter. It pleased me that you have also found the ‘Book of the Poor’ to be Kasprowicz’s most beautiful work; I am also very grateful for the words of critique about the method in my article. It is because of this criticism that I am so late in replying, because I wanted to find a clipping from my old article (about Kołaczkowski) in which, as it seemed to me, there would be a response to your accusations; I have been searching for these for a long time, and now that there is this issue you have addressed (I am sending you these sections). – Well, sir, this is the way it is The analysis of the “style” and “structure” of a poetic work has been my critical ideal for a number of years. I was so absorbed in analytic literature of this type that it amazed me when I read in your letter that this literature is almost non-existent. It is, de facto, it may be that it just seldom breaks out to the forefront of “wider” criticism: and this is characteristic! It is a kind of criticism which is needed, but far from sufficient. One cannot deprive of history anything that expresses the life of the spirit. And these stylistic-structural studies, while stemming from the right assumption that poetry is an intuitive and emotional matter, instead of a rational one, completely dehumanizes it – by rejecting everything that is intellectual. All that is lest of the poet is either a magician or some force (even a moral one) whose mobility is admired, but as to which direction absolute désintéressement is announced. In my opinion, that is, to an extent, what happened to Kasprowicz in a the otherwise beautiful book by my friend Kołaczkowski. He considers the desire for absolute values, the pursuit of certainty, the conviction of having that certainty to be the most outstanding feature of his poetry and the whole of his nature,. But as to what that certainty, or rather subsequent certainties are in Kasprowicz’s case – he does not really care. And yet this is what relates this poet to each of us, the history, the basis of humanity. The high emotional tension, the peculiar “appearance” of his world – these are the only, poetic, things that we can never completely grasp, but the “road” to them is built of universal human affairs – capable of being intellectualized.

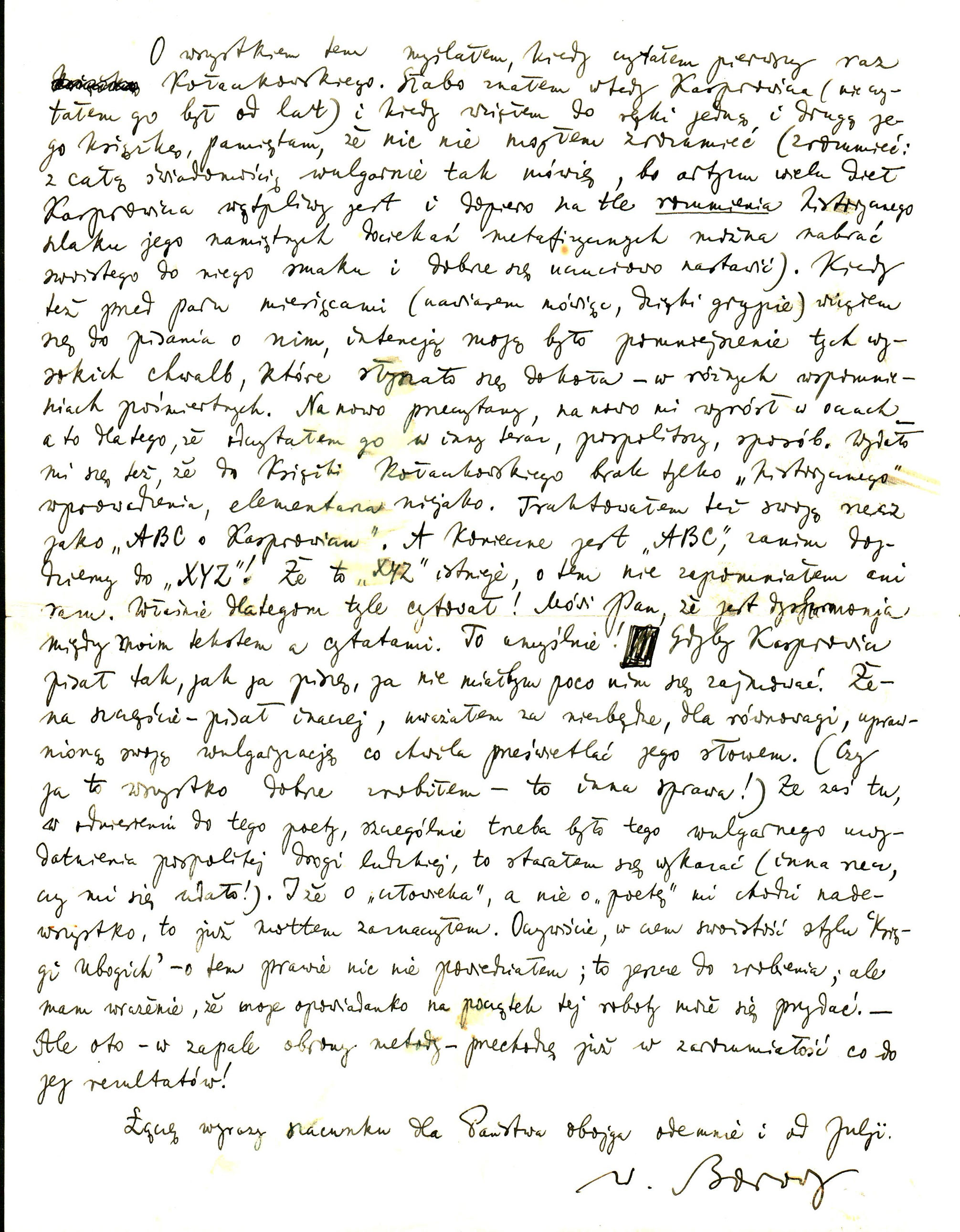

n Such were my thoughts when I first read Kołaczkowski. I was not very familiar with Kasprowicz at that time (I had not read him for years) and when I took a look at both books I remember that I could not understand anything (understand: I am saying this in such a vulgar way with full awareness, because the artistry of many of Kasprowicz’s works is doubtful and only in understanding the context of the historical path of his passionate metaphysical inquiries can one get a taste for it and have a positive attitude towards it). So when I took to writing about him a few months ago (incidentally, thanks to influenza) my intention was to diminish those high glories that could be heard all around – in various posthumous recollections of him. Read again – it grew on me, and this is because I read it in a different, more common, way.

n It also seemed to me that Kolaczkowski’s book lacked only a “historical” introduction, a primer of sorts. Hence I treated my work as an “ABC on Kasprowicz.” And an “ABC” is necessary before we get to “XYZ”! That this “XYZ” exists I have not forgotten for a minute. He quoted so much for the people! You say there is disharmony between my text and quotes. It’s deliberate! If Kasprowicz wrote the way I write, I would not have had to deal with him. That, luckily, he wrote differently, I found it necessary, for balance, to shed the light of his word on my legitimate vulgarization every now and again (if I managed to do it well is another matter!) That here, in relation to this poet, this vulgar highlighting of the common human path was especially needed was what I was trying to show (another thing whether I succeeded!). And my focus on the “man” instead of the “poet” I have stressed already in the the motto. Of course, I have not yet expressed wherein lies the uniqueness of the style of the ‘Book of the Poor’; that remains to be dealt with; but I have the impression that my little story may come in handy at the beginning of this work. But then look – in my passionate defense of the method – I am already getting conceited when it comes to its results!

n My deepest respects to you both from me and Julia

n n n n n n W.Borowy