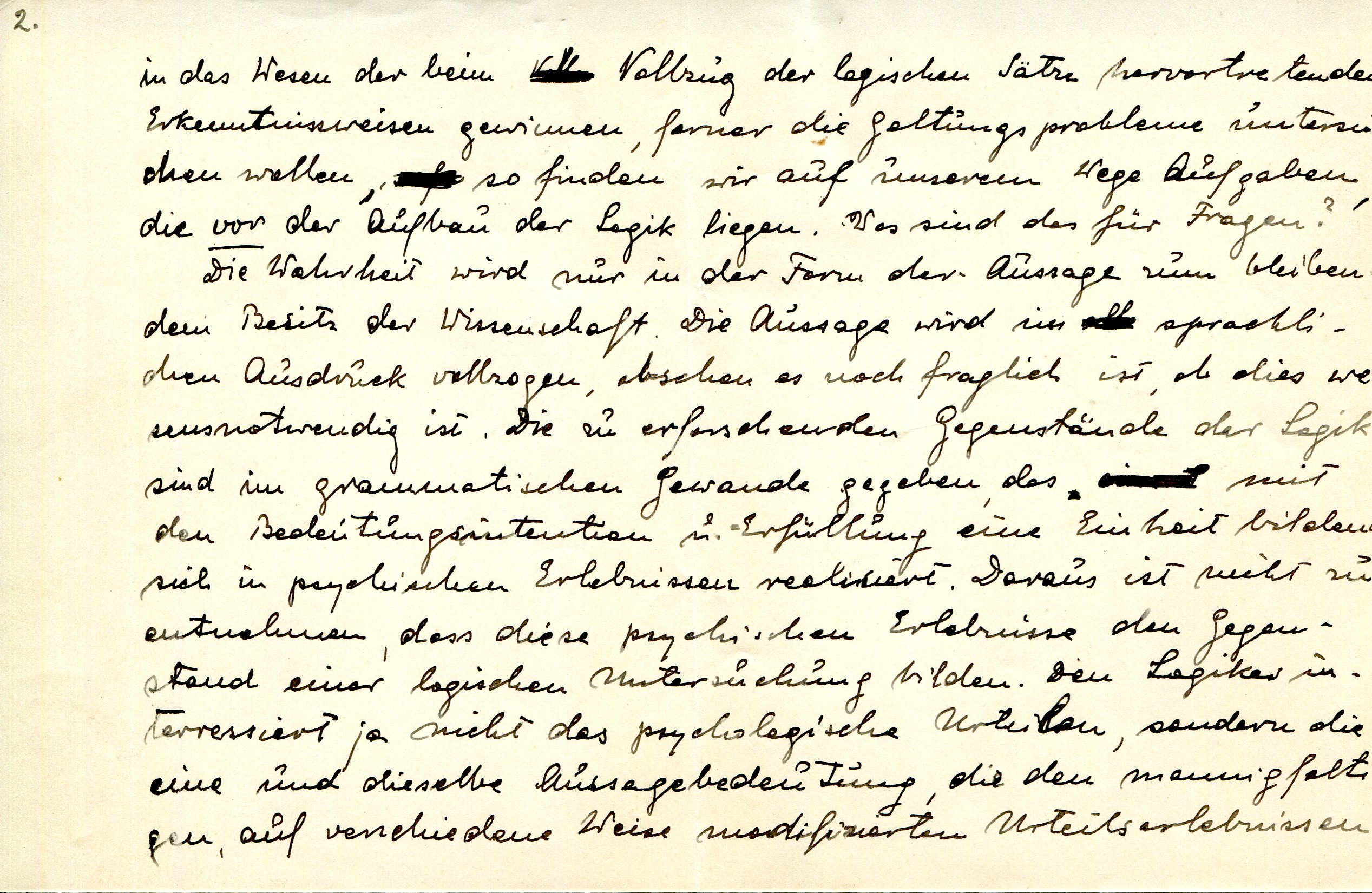

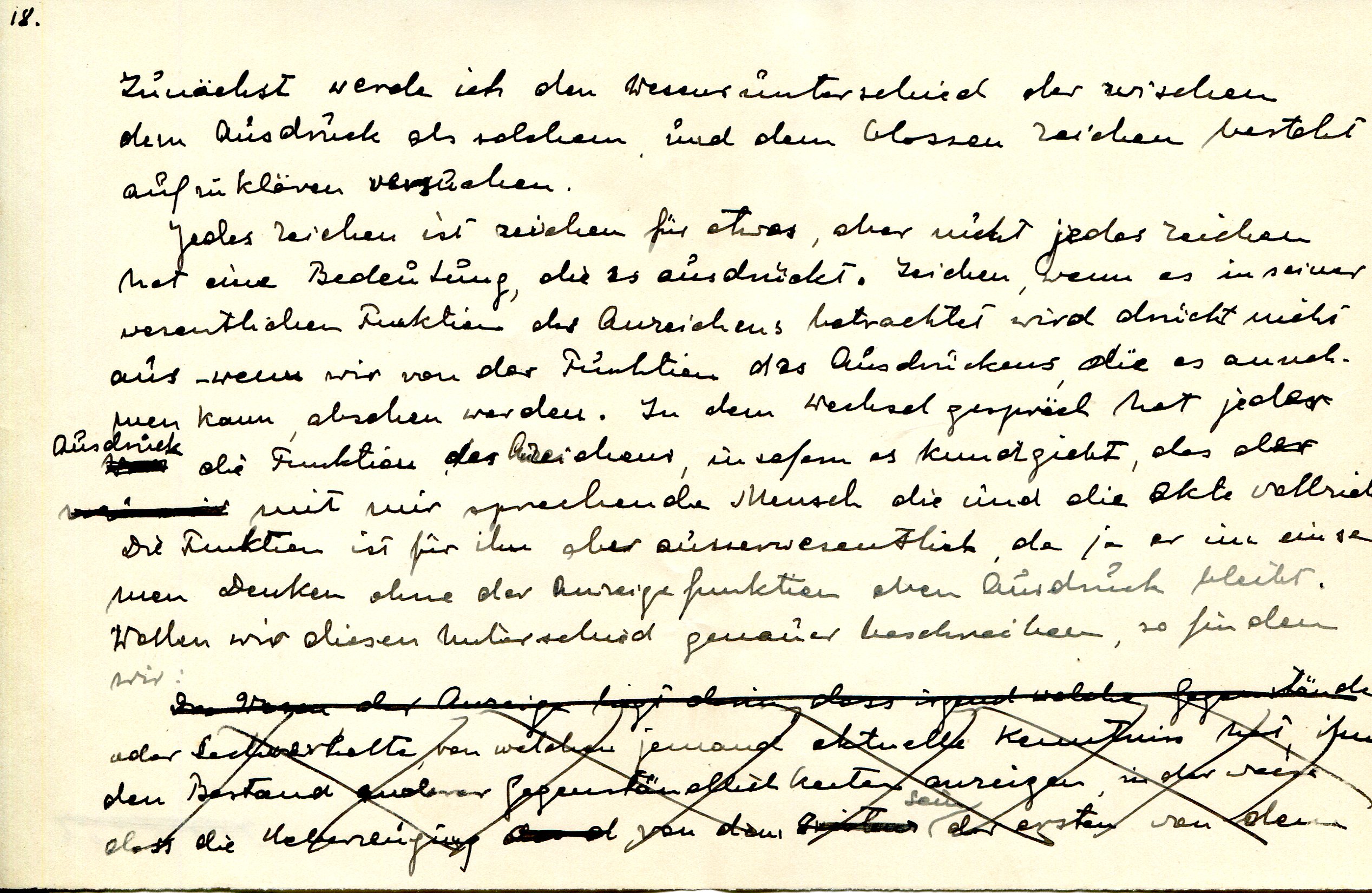

Lecture of Roman Ingarden on Husserl’s seminar 26.10.1913

Husserl’s seminar

Ingarden’s notes

Trans. Sonia Kamińska

26 X 1913

When it comes to psychologism in logic, we have come to such a result, that every grasp of logical objects (like concept, judgment, conclusion) as psychic facts on one hand distorts the sense of logical sentences, on the other hand it must lead to contradiction and scepticism. The grounding of every logic as a kind of normative science lies in pure logic, whose laws do not concern thinking – from the viewpoint of “how it is” or “how it should be” – but what is thought, the ideal content (Inhalt). After this statement one could acknowledge, that everything is done and we can, without further ado, proceed to the problems of logical content. However, if we develop logic not only as a kind of mathematic science, but if we want to explain it in a philosophical way, i.e. get an insight into the essence of the ways of cognition appearing by the introduction of logical sentences, and then to investigate the questions of evaluation (Geltungsprobleme), then we will find on our way tasks that are ahead of the construction (Aufbau) of logic. What are these issues?

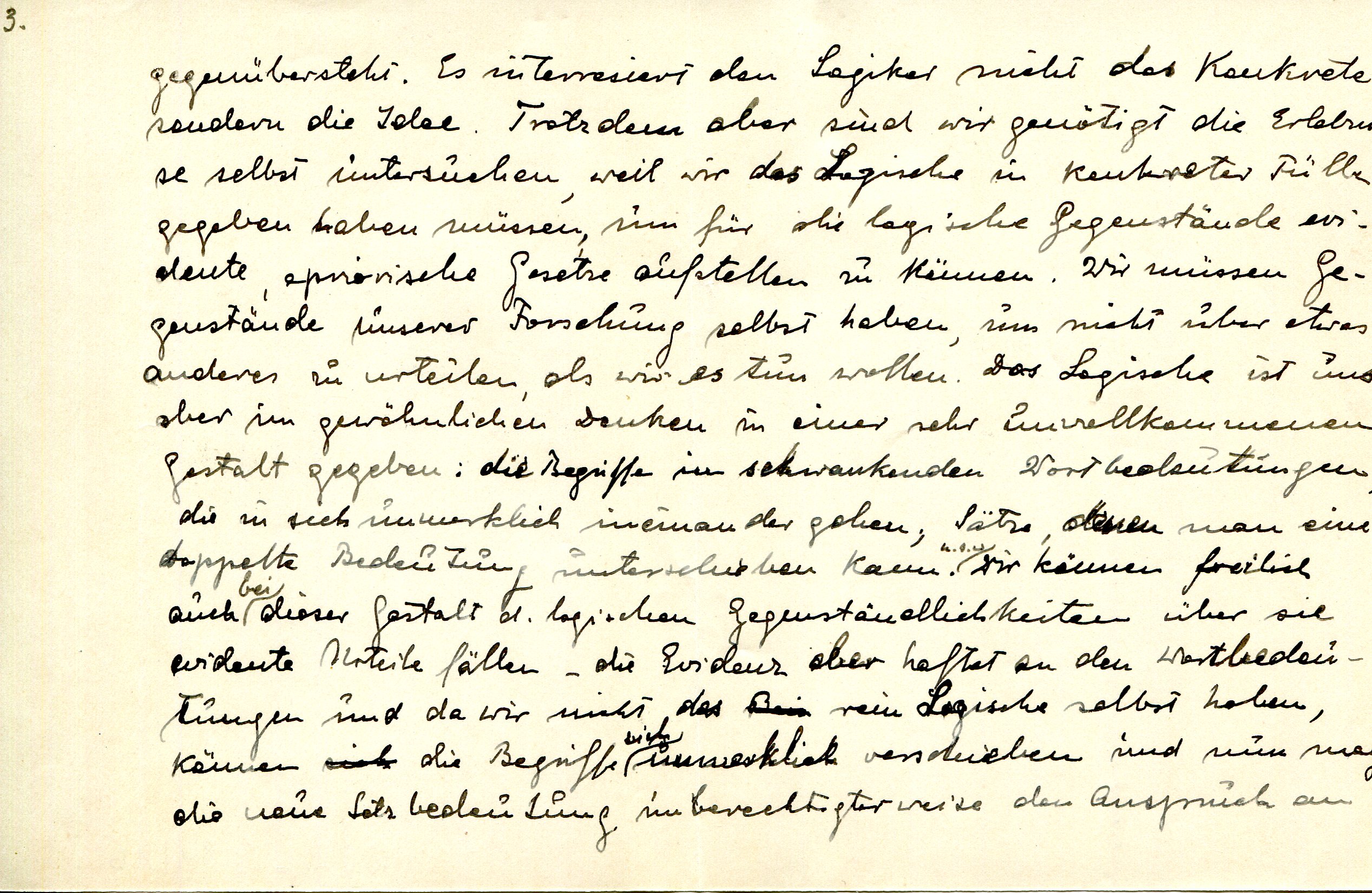

The truth will remain within the possession of science only in the form of a statement (Aussage). A statement will be linguistically expressed, although one can still wonder, whether it is essentially necessary (wesensnotwendig). Logical objects, that are to be examined, are given in a grammatical form, that fulfils itself in mental phenomena (in psychischen Erlebnissen) alongside with a semantic intention (= a fulfillment of a unity). From here, it is not to be concluded that these mental phenomena (psychische Erlebnisse) are an object of a logical investigation. A logician is not interested in mental judging (das psychologische Urteilen), but only in the meaning of the statement (Aussagebedeutung), that corresponds to manifold, multiply modified, phenomena of judging (Urteilserlebnissen). A logician is not interested in what is concrete, but in what is ideal. Despite that, we are nevertheless forced to investigate the phenomena themselves, because what is logical has to be given in a concrete fullness in order for us to establish the obvious, a priori laws for logical objects. We need to have the objects of our investigation themselves in order not to issue judgments on something else than we really want. However, what is logical is given to us in simple thinking in a very imperfect form: the concepts merging unnoticeable in the faltering meaning of words; sentences in which one can investigate a sort of double meaning, and so on. Of course, by this form of logical figurativeness we can stumble over the obvious statements – yet, obviousness lies within the meanings of words and because we do not possess what is purely logical, the conceptus can unnoticeably differentiate and thus the new meaning of a statements can have an unauthorized claim to obviousness. Let us, without checking, formulate logical statements from all these uncertainties …[i]. We must thus find a way that will offer us logical ideas in clear and distinct way. It is a way one should follow from “words” to the things themselves in order to arrive at opinions [present in] the meanings of the objects of thought. This means nothing else than to go back from the investigated figurativeness to consciousness. Instead to discuss what meaning is, we prefer an act of meaning and while experiencing this act, considering it – we understand what it itself – as the saying goes – “wants”. We keep on practicing this descriptive analysis as long as this is necessary for the full determination of logical concepts.

Let us give an example here. When we express a statement (Urteil), e.g. “This table is black” and we look at the experience that is being realized during the expression we will at once see that different – as they are called – “parts” can be separated from the entirety of experience and play their own part. When I say “This table is black”, I thereby give the listener to understand that a phenomenon / experience called judging (Urteilen) has realized in me. My judging however is not what my judgment means. When I repeat my statement (Satz) again and again, I have realized many acts – that, however, what I have pulled out [of it] is one and the same, in the strict sense identical content of a statement (Inhalt der Aussage). And again: this content is something else than the object being judged (worüber geurteilt).

And this is how – anyway, with a different degree of precision! – we can proceed and during such an analysis achieve at logical figurativeness. But we will be asked a question at once: isn’t it what we have been fighting off before – psychologism? What else are we considering here if not mental contents, facts? Isn’t my judging (Urteilen), stating (Aussagen), etc., a mental state of a person equipped in various capacities and dispositions? Are the adherents of psychologism right?

We see that the possibility of a philosophically explained logic is in question here. Therefore, we have this one and only way of explanation – go back to the “consciousness of something” („Bewusstsein von“). If this is so and the path necessarily leads to psychological facts, then logic as a philosophical discipline is in principle impossible. Its laws are then only the unauthorized presentations that we want to question as such. On the other hand, from the sense and the validity of the laws of logic it follows: firstly, that it would be contradictory to consider laws of logic as untrue, only idealized fictions (we do have a direct access to the [fact that] they are true, don’t we?), secondly, that their grounding must be absolutely necessary, a priori – hence, not psychological, a posteriori, and experience-wise. It is also true that the experience and epistemic grounding is possible only the long way around of “being given in consciousness”, there must be thus an a priori knowledge of consciousness, hence the analysis of consciousness and psychological investigation must mean something else.

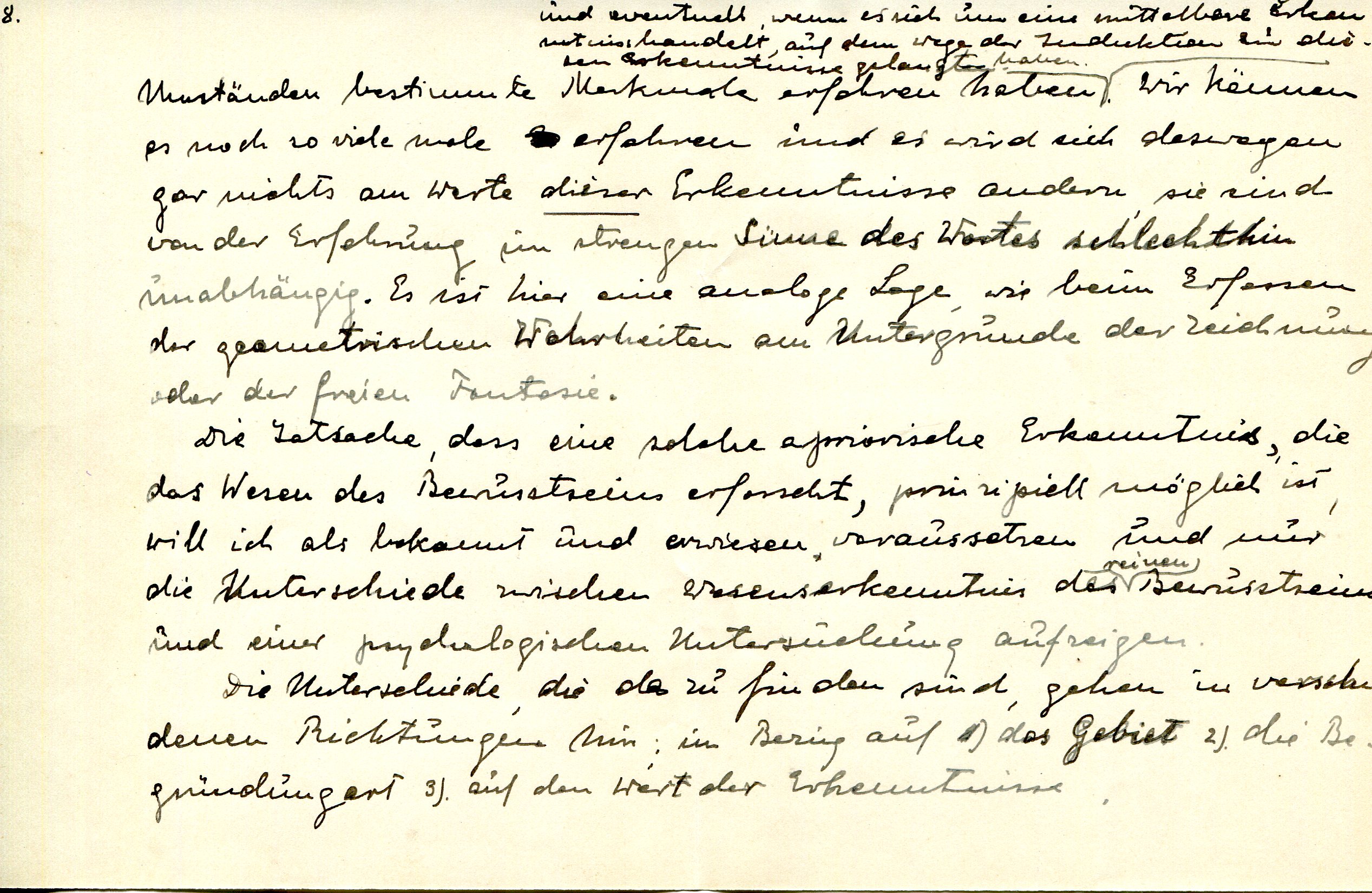

This conclusion is indeed true and we can convince ourselves if we take an experience and consider it as pure, in itself. At first glance, different divisions and dependencies appear, about which it is useless to speak, that they are grounded through inner experience, that means that the respective insights (Erkenntnisse) are valid only because many times we have experienced this and that in specific circumstances and maybe, when it comes to indirect knowledge, we have arrived at these insights (Erkenntnissen) via induction. We can still experience this many more times and absolutely nothing about the value of these (Erkenntnisse) will change, they are – in a strict sense – totally independent from experience. This situation is similar to learning truths of geometry on the basis of a drawing or pure phantasy.

The fact, that such an a priori cognition that investigates the essence of consciousness is at all possible, I wish to claim known and proven, and only indicate the differences between the essential knowledge of pure consciousness and some psychological investigation.

The differences we find there, branch in different directions; on account of 1) area, 2) way of justification, 3) value of cognition.

With regard to the first one, i.e. area, one needs to say the following: the last objects of psychology – and it concerns both, the empirical and the so called descriptive – are individual units of empirical facts with a time limit. A psychologist investigates human experiences that belong to the real world and partake in causal relations with other real entities (Realitäten). They can depend on various dispositions. She investigates mental states in which the capacities of human organization are disclosed. The only difference between empirical and descriptive psychology is that the first one wants to explain the mental phenomena with the courses of psycho-physical phenomena, on the path of natural sciences (also grammatically[ii]); whereas the descriptive one investigates the mental phenomena themselves, and tries to explain, and describe what is immanent to them. Nevertheless, both claim that consciousness is something real that belongs to the world. The objects of the analysis of consciousness art the ideal species of pure consciousness. Perception which is investigated in the phenomenological attitude is not this or that, occurring here or there, mine or belonging to someone else. It is not a perception belonging to human organisation either, it is not a mental state, but it [is] a pure experience. This perception is such in general, in truly universal generality, it is a real essence. It does not belong to the real world, it is not a fact. It is one and the same for endless amount of respective possible realizations, is timeless and does not stand in any relation towards the real space.

This being the case, the following charges will be brought:

Psychology does not want to investigate this or that experience, this or that perception, memory, but a perception “in general”, memory “in general”, etc. It wants to establish general laws for the figurativenesses. Aren’t these – therefore – the same objects as those intended (intendierte) by the cognition of human consciousness, only called differently?

This has to be answered:

Firstly: the figurativenesses of both sciences are different. This difference lies not only in the way in which the phenomenology of pure consciousness wants to grasp the essence of experience. The objects considered by psychology can be analysed in essential generality. The outcome of this analysis is not a science on the essence of consciousness in an episteme sense, but a science about the essence of the constitution (Zuständlichkeiten) of the human I, i.e. an ontology of mental phenomena. Secondly: this psychological “in general” and the generality of psychological laws mean something entirely else than what we have in mind (was wir im Auge haben), when we conceive the essence of perception “in general” of a pure perception. General concepts of psychology are the concepts that come into being via induction. We have a row of objects or phenomena. We count some features that – in experience – always appear in the same circumstances into one class concept (Klassen-Begriff). These are not only the unclear concepts that can count for us within the scope of the observation precision. The scope is determined here by all the specific, individual objects that fall into the respective class. This “in general” here means only: all the cases that have really appeared or will come into effect. Pure, absolute “in general” is annuled by this presupposition. Likewise the “generality” of laws whose parts build up such concepts, are restricted to the sphere of the real world, is conditioned, it is valid only under such a condition that the figurativenesses really exist.

However, in phenomenology we do not have class conceptus but rather species conceptus. The scope of these concepts is eidetic, i.e. in the end it is eidetic singularities that fall into it (when the respective concept itself is the lowest difference and has a scope at all). For every essence there is a scope of possible, individual solitarinesses (Vereinzelungen). This “in general” (e.g. a perception “in general”) concerns all these essences, that stand below the essence “perception” as is possible metamorphoses. This “in general” is necessarily abstract, the question about the existence of that what it at all concerns is totally irrelevant. The general law isn’t here a law for all really existing individuals that belong to one class, but for all essences that stand on different levels of abstraction, alternatively – of being specific, that fall under the highest essence for which the relevant law is valid.

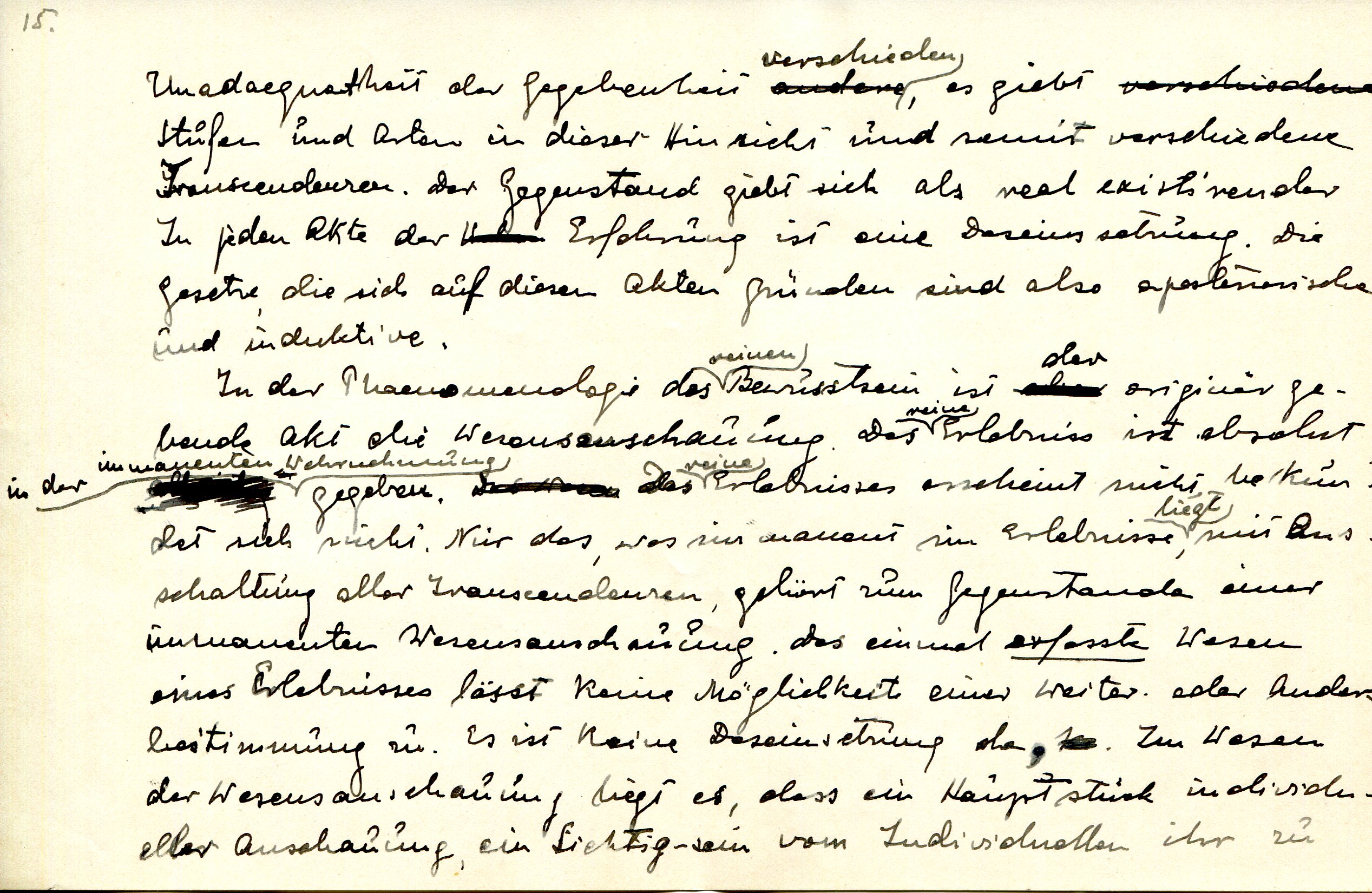

The next difference that occurs between the phenomenology of pure consciousness and psychology is the way of justification. Indirect psychological insights (die mittelbaren Erkenntnisse der Psychologie) are based on the direct experience. Perception (especially the so-called “inner” one) is here the act in which the mental states become source facts. A mental act occurs in the ordered variety of confirmations. This state itself is not given to us. The [fact] that the objects constituted in the acts of experience can never be adequately given belongs to the essence of these acts. There is always a possibility of new experiences that not only determine the object more closely, but they can also determine [it] differently. By different types of realities there is a different inadequacy of the given. There are levels and kinds of it, and thereby different transcendencies. The object presents itself (gibt sich) as really existing. On each act of experience falls one existential settlement (Daseinsetzung). The laws that ground themselves on these acts are thus a posteriori and inductive.

In phenomenology of pure consciousness, the source act is the outlook on the essence. Pure experience is abstractly given in the immanent perception. Pure experience does not present itself, does not reveal itself. Only what sticks immanently in our experience, except transcendence, belongs to the object of an immanent outlook on the essence. An essence of an experience – if once grasped – leaves no further possibility of further or different determination (Bestimmung). There is no existential settlement there. In the essence of the outlook on the essence lies …[iii]. No determination of an essence is possible without a free possibility of taking a look at (Blick-wendung) “the right” individual, but this “the right” individual is only an example, using which we make essence visible; however, it is not an object of cognitive act itself. The knowledge of an essence is a priori, respective truths do not contain any statements about facts. Experience in free imagination is a nonsense, nevertheless, surely there can be an outlook on an essence in free imagination.

Finally, we arrive at the difference in the value of the both type ox experiences.

The laws of psychology are not true but only probable. Their probability grows only thanks to the number of cases observed, it cannot however – and this is crucial! – turn into absolute validity (Geltung). The laws say only that usually in specific conditions specific qualities appear or that – with bigger or smaller probability – we should not be expecting them. These are only actual arrangements, that in principle could sound totally different. This means: other possibilities are not – in principle – excluded, only their realizations are actually excluded.

The experiences of an essence in the sphere of consciousness are abstract, true in the absolute generality and necessity. Every negation of an essential law (Wesensgesetzes) gives absurdity[iv].

[i] Unfortunately, this sentence is elliptical. Something is missing there, it is hard to translate unambiguously. See the transcript – transl. note.

[ii] The translator is not entirely sure whether it is really “grammatical”. This doubt follows from the quality of Ingarden’s manuscript – transl. note.

[iii] Unfortunately, this sentence is elliptical. Something is missing there, it is hard to translate unambiguously. See the transcript – transl. note.

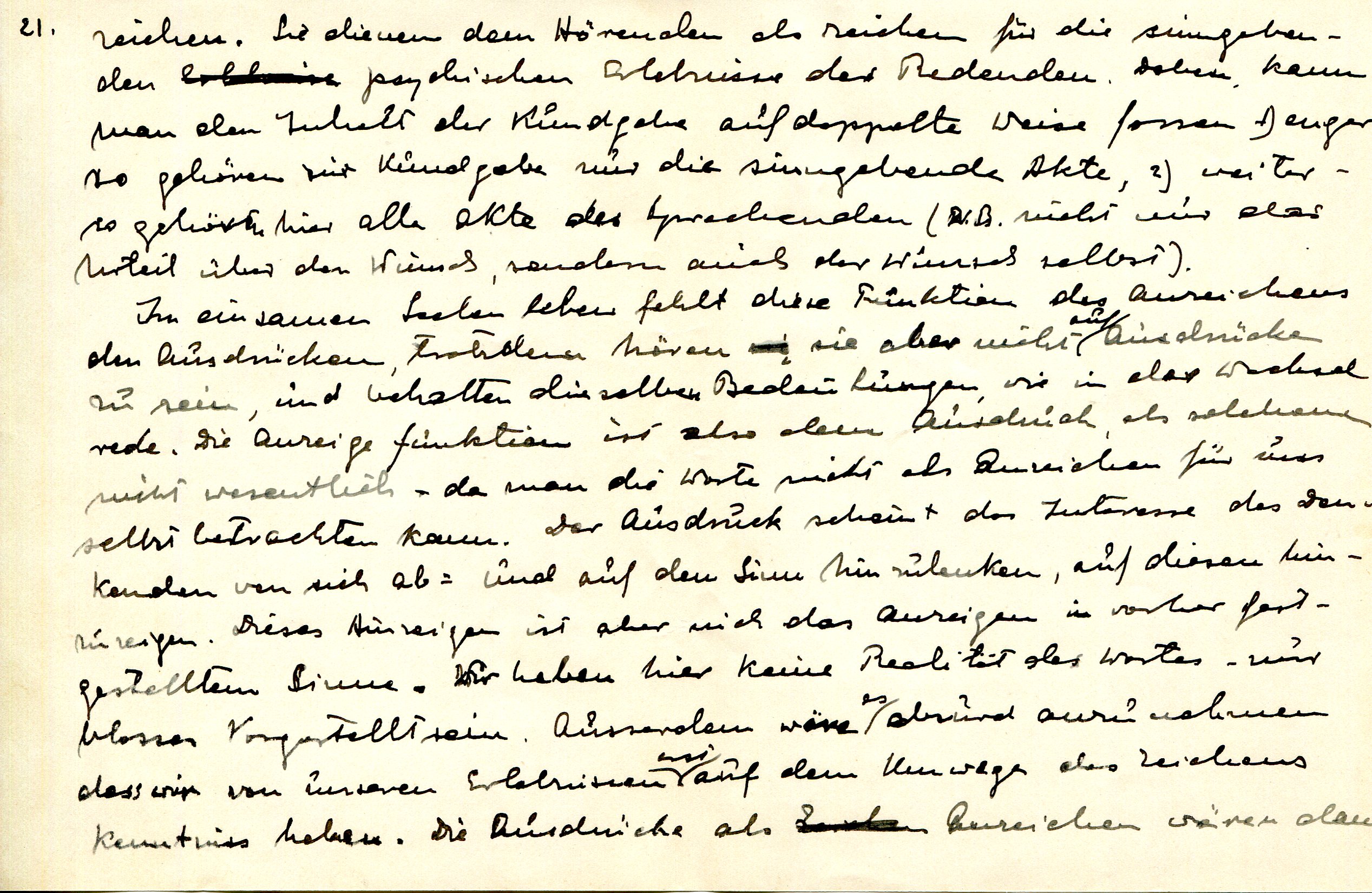

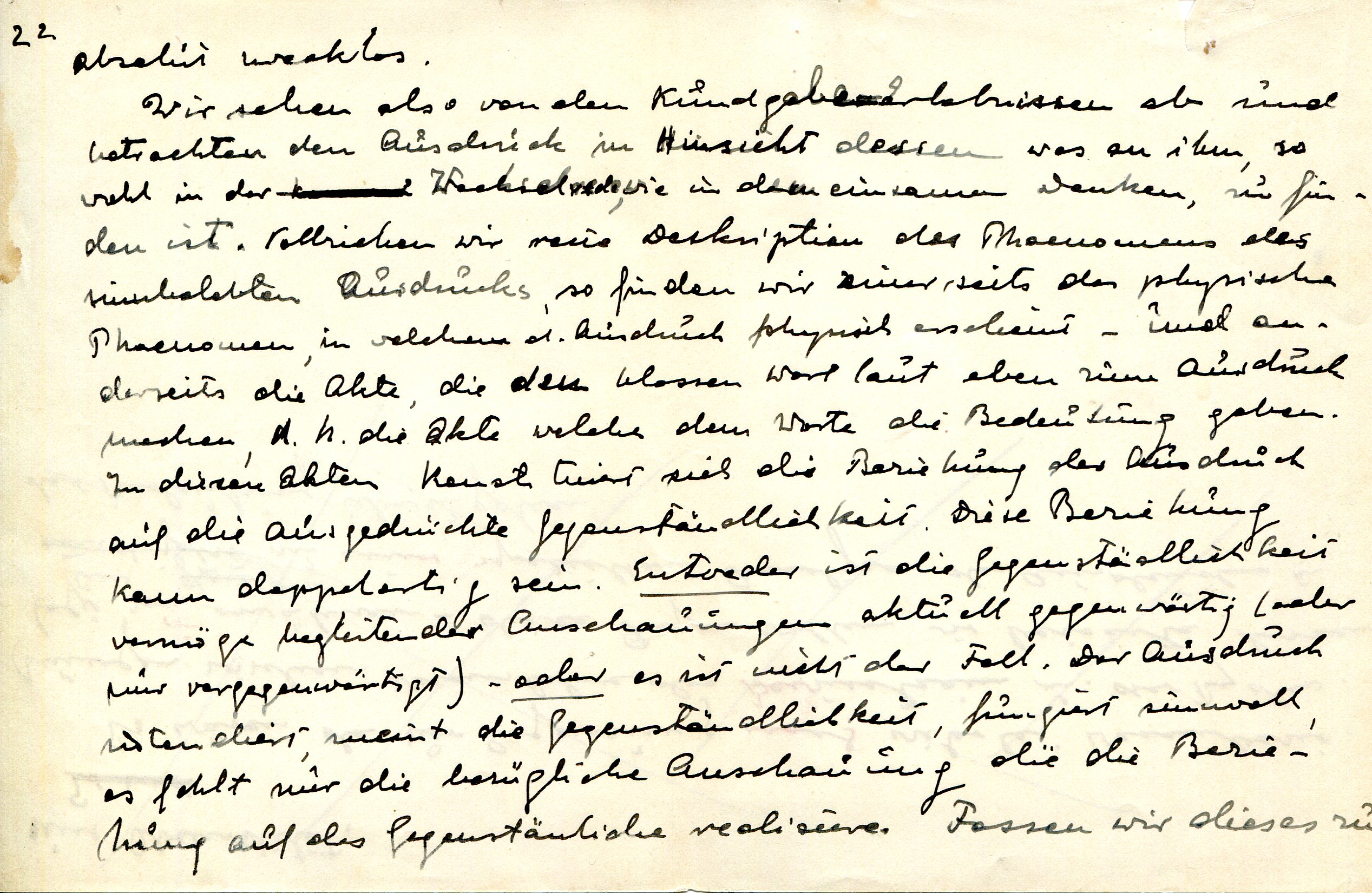

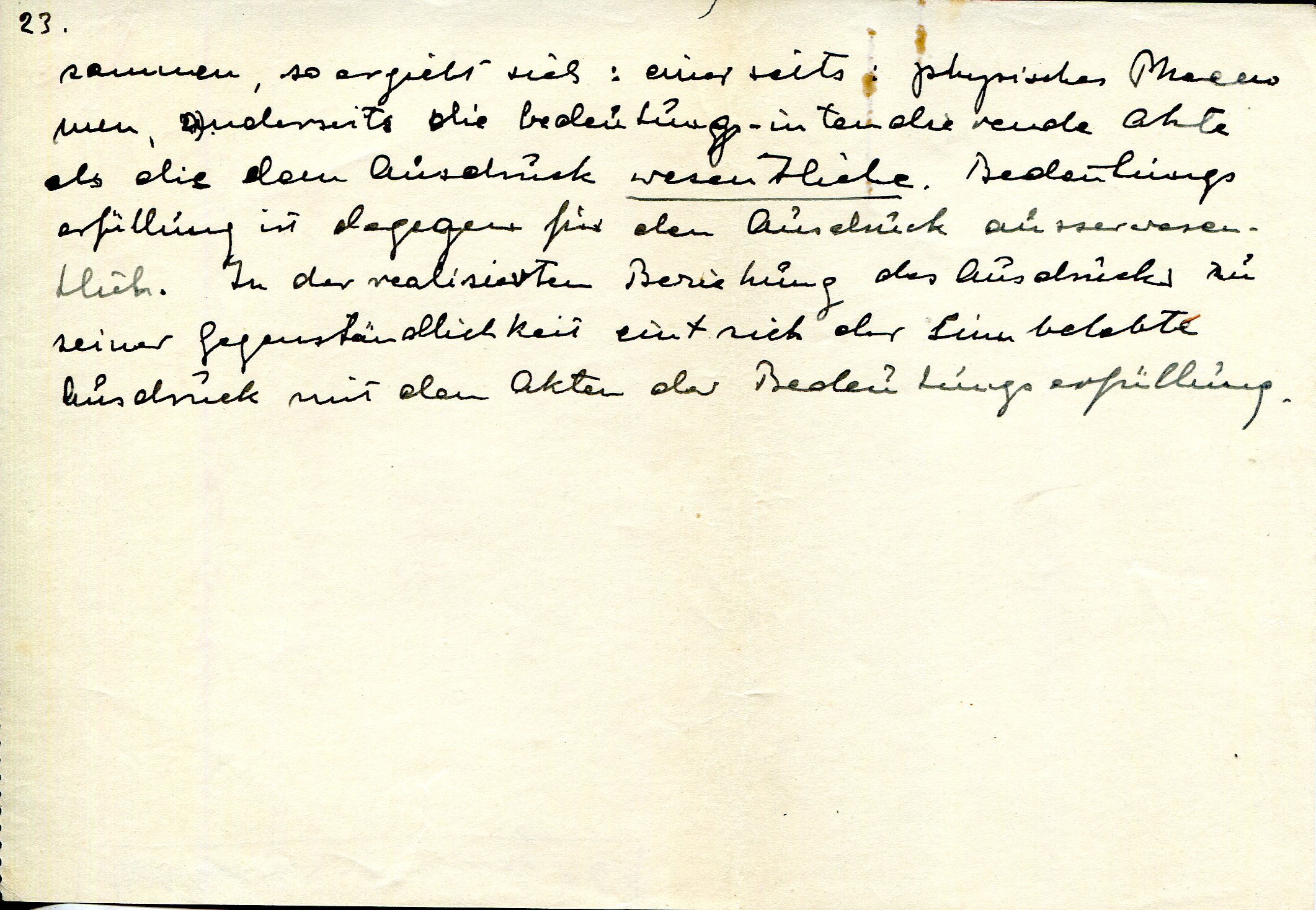

[iv] This translation encompasses the slides 1-17, up to the visible underline on page 17. The following slides up to 23 are incredibly difficult to decipher and unclear in their content. Sentences are elliptical and the thread breaks often. This can be a result of starting a discussion or changing a subject during the seminar. Both can explain the quality of the text – transl. note.