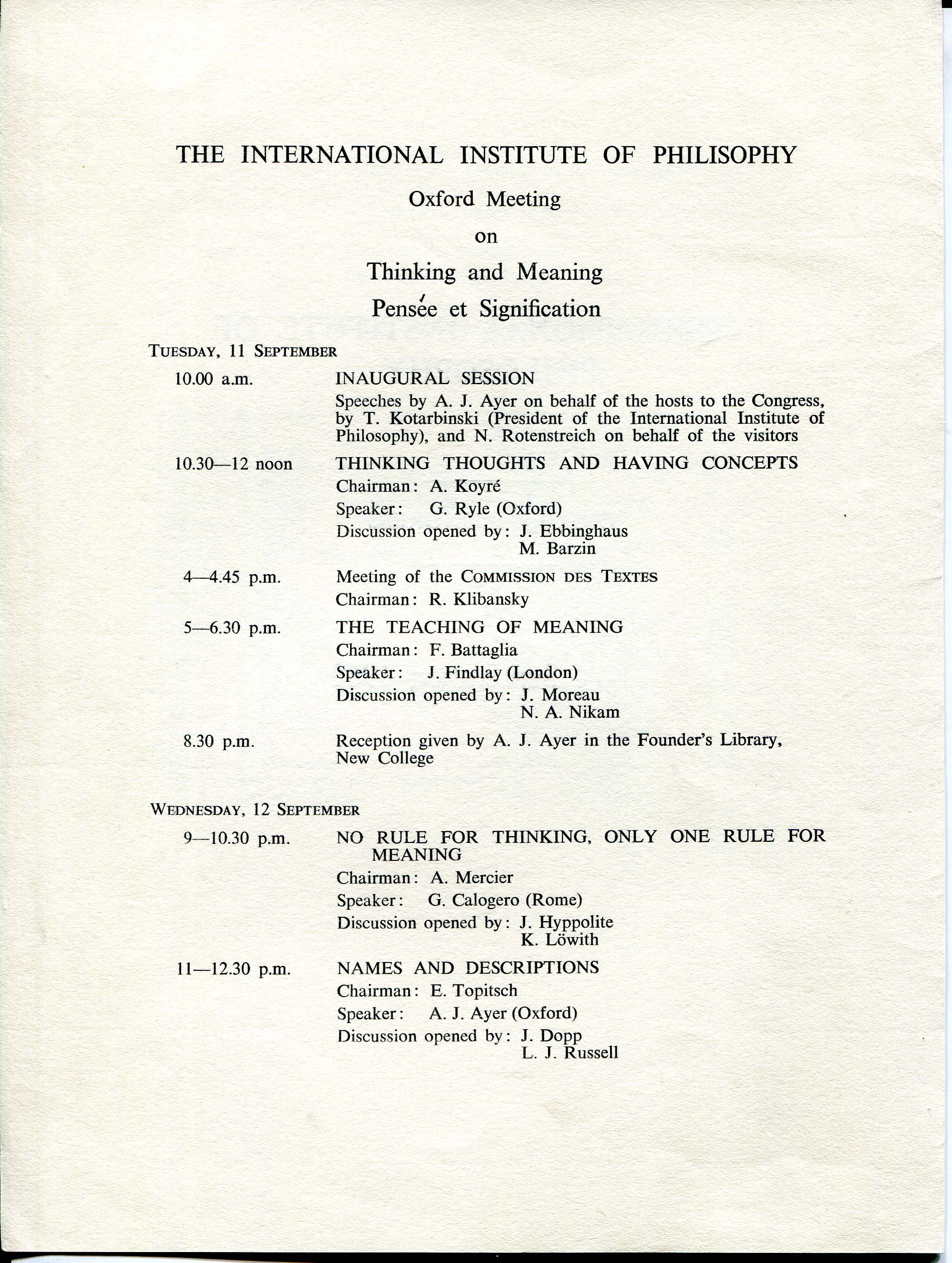

Lecture of Roman Ingarden in Oxford nd.nd.1962

Word as an element of language

Roman Ingarden

The issue of the meaning of a word or the meaning of a sentence is very difficult to tackle if we fail to notice various linguistic phenomena. De Saussure’s distinction between “utterance/word” and “language” is not sufficient. A distinction should be made between: 1) speaking = processes of expressing reality by speech or thought; 2) specific linguistic units = utterance, speech, improvisations, which arise in the speaking process; 3) permanent (written) linguistic units = literary works or parts thereof; 4) specific language (French, Polish) or special languages (slang) 5) “normalized“, “correct” language; 6) a system of linguistic norms (rules) of two different types, such as “principles” that say, “how” to speak or write, and “principles” that determine language facts relevant to a particular period; 7) language as a unique creation of humanity.

In each case, the structure of the whole and its elements is different, as are the properties and functions of those elements. I shall limit myself here to a description of facts corresponding to No. 4.

Language is an intersubjective unique unit that arises in historical time and in the specific human society that creates and transforms it. Each language has its own distinctive features that distinguish it from other languages. It evolves decisively not only under social and political, but also individual conditions. As a result, it has a different history from that of speaking and of literature written in that language. It also differs from the sets of units specified in points 2 and 3. The essence of language understood in this way is the main issue of the philosophy of language, however it will not be the subject of our considerations.

In order to initially determine what language is, it is necessary to indicate its units, namely: 1) a (varying over time) set of words /vocabulary/ that always have a (typical) sound and one (or many) meaning (meanings); 2) a set of “grammatical” words (declension, conjugation) that make up a particular system; 3) a collection of typical “ways of speaking”; 4) a system of syntactic functions; 5) a selection of possible types of sentences and utterances*; 6) a set of possible functions of expression and linguistic influence on others. All these “forms” of a particular language are engaged in the process of gradual evolution and transformation.

Then we need to explain what a word is as an element of a particular language (word1) and what its role is in that language (by word2 I understand word as an element of a linguistic entirety).

Word2 can basically contain many “similar” words in a single or various linguistic units (for example, the word “father” is “repeated” many times in Corneille’s Le Cid). Each word1, on the other hand, is unique in a given language. What determines its identity is a specific (typical) sound and specific meaning (sometimes several meanings, but this homonymy cannot exceed certain limits if we want the identity of the word not to be obscured despite the identity of the sound). This is the case, for example, if the meanings belong to different semantic categories and “have nothing in common with each other.” In this case, the identity of the sound is only apparent, so we have two different words (nine = neun and new = neu, dirty = schmutzing and sala = der Saal, his = sein and sound = der Klang[1]. The sound of the “same” word1 in different possible dialects of the same language may differ, but not to such an extent that a listener no longer perceives it in the aspect of the same typical sound.

Between the word1 and the same word2 there are some differences in sound and meaning /differences in the sound symbol/ of which the most important are: a) when we “use” word2 in a specific linguistic unit, certain modifications of its new form emerge correctly in its sound aspect that attach to the sound of the “same” word1. Here are their sources: 1o other words2, which 1) surround in this unit of language, provoke the emergence of – next to the sound typical of this word – new sound symbols varying in accordance with a given environment; 2o the position of a given word in a sentence and its syntactic function contribute to different accenting; for example, the subject of a sentence is stressed differently from an addition; the pitch varies depending on the position of the word, according to the so-called “sentence melody” characteristic of the language in question.

The same word1 lacks its modifications, but recognizes them: all possible modifications do not change its identity; 3o) The grammatical and syntactic functions of word2 include transformations of the grammatical “form” of word1 (declension, number, gender, person, time, etc.) Word1 does not have all of its sound forms, it only allows them as certain possibilities of variation or supplementation of a sound. This typical fundamental sound usually “breaks through ” all modifications of word1 when it is used in various specific linguistic units. It stands out as a characteristic aspect of this word1, a decisive sign of its individuality and uniqueness in a particular linguistic system.

- b) the differences between word1 and the same words2 are both structural differences and differences in the way they are created. Word1 is a well-defined and isolated whole, word2, on the other hand, “related to” [or], better, “connected” in its meaning with other meanings, in the entirety of the meaning of a linguistic unit, which, although being articulated, constitutes a whole to a higher degree.

The differences between word1 and word2 that appear in the internal structure of meaning are much more important. These differences vary depending on semantic categories, they are different, for example, for a verb and a noun. I limit myself here to the description of those concerning the noun.

The meaning of noun1 contains various elements, including: 1) a nominal index directed at the named object, 2) material content, 3) formal content, 4) intentional moments, by means of which the noun can perform various syntactic functions in higher linguistic units, for example in a sentence. Material content, which determines the properties of the named thing, contains several moments of two distinct nature: constant and variable (general moments and moments of individual features). They can be found here in their current state or in their potential (explicit or hidden). If we limit ourselves to general names, we can say that the nominal index of the meaning of a single name (mot1) is potential and variable. On the other hand, in the case of noun2, this index is present and stabilized, or at least limited in terms of its variability.

Some variable moments in an isolated name (e.g. Triangle) change into fixed moments if the noun (as a word2) becomes an element of a sentence (in an equilateral triangle four single points overlap). The context of the the noun actualizes some potential moments of the material content of the meaning of noun1. Purely potential moments of the isolated noun are actualized in various ways depending on the function that the noun performs in the sentence (as word2), for example as a subject or as an object or as a descriptor of the subject. Similar differences can be found in the meaning of a verb (taken out of context or in context) or in the logical factor.

The facts we just mentioned conclusively show that word1 is something other than “the same” word2 in a completely determined context. Two questions arise: what is word1 as an element of a particular language and what is word2? There are many answers, and the conditions for learning the meanings of individual words and different language constructions, and thus also “teaching of meaning” – an issue that J. N. Findlay reflects on – depend on the answer to this question.

There are many concepts of word1. The most important and, possibly, the most well-known ones are the following:

- Word1 is exactly the same as specific cases of its “use” in different contexts, and therefore the same as word2. This concept is inconsistent with the facts mentioned above.

- Words2 are units, examples of type, while the word1 is a type of these units. Depending on the philosophical doctrine, word1 would be a Platonic idea, in a sense, or an accident in the sense of certain empirical concepts. A specific language, defined as its purely lexical part, would not consist of words, but of their types to which words, such as individuals taking part in specific linguistic units and closely related to speech, would correspond.

- Word1, in contrast to correlative words2, would be the general name of the latter. In this case, language, defined as its lexical part, would only be a meta-language, consisting purely of nouns the subject of which would be words2 present in specific linguistic units.

4a) Word1 would not be a word, but instead a rule defining the properties of words2 which determine how they are used. In this case, language, defined as its lexical part, would form a set of sentences defining the general properties of words2 – units. These – normatively understood – principles would create guidelines, according to which sounds and meanings of words2 should be created. From this point it would be easy to enter into the normative concept of language, which views it only as its normatively understood grammar.

4b) Word1 is nothing but a consistency, a summary of a certain number of individual cases in which it is realized in concerto. These cases of its “realization” are nothing more than “words-units2“. In this case too, language, defined as its lexical part, would not consist of words, but of something distinctly different from them. It is not easy to decide what the features of this “abstract” consistency should be. Its concepts depend on the general philosophical doctrine, which would apply to the abstract regularities of each type. [2]

5) Both word2 and word1 are deliberate products of a specific thought, but word1 is a higher order derivative. This stems from a specific historical process that requires mutual understanding between members of the same speech community. Part of this process is reflection on elements of linguistic units and conscious construction of the linguistic system, both in linguistic practice itself and in language-building activities as a tool for various purposes (for example, in order to cognitively control reality, exert influence on others, agree on joint action, specify artistic values, etc.). According to this concept, language, defined as its lexical part, consists of words1, but words /vocabulary/ attributed with generally much richer meanings than words2 and – at the same time – meanings containing many more potential moments. And the sound of such a word is the typical sound form (Gestalt), which individual sounds of modification of various dialects and sounds corresponding to individual words are coordinated with, similarly to the individual concretizations occurring in different possible variations.

I cannot fully discuss these concepts here. However, I must say that in my opinion only concept 5 is acceptable, of course in a more elaborate version than can be presented herein.

_________________________________

Roman Ingarden

[1] Originally: neuf = neun et neuf = neu, sale = schmutzing et la salle = der Saal, son = sein et le son = der Klang. (transl. note)

[2] Points 4a) and 4b) are possible interpretations of Trubecki’s point of view.