Letter to Kazimierz Twardowski written 02.06.1920

Warsaw, Złota 41, apt. 4.

2/6/1920

Honourable Professor!

Thank you very much for your kind letter dated 21 May of this year. I apologise for not replying until now. However, now – at the end of the school year – I have so much work that it’s only with difficulty that I can find time to attend to personal matters.

To deal first of all with the matter of buying books, I hereby inform you that tomorrow (3/6) I’ll pay 21.60 marks by means of a P.K.O. [Powszechna Kasa Oszczędności; Universal Savings Bank] check to Movement’s account, as payment for the following books:

1) Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 7 M.

2) Błachowski, Nastawienia i spostrzeżenia [Attitudes and perceptions], 2.10.

3) ″ O wrażeniach położenia etc. [O wrażeniach położenia i ruchu; On impressions of positions and movement], 4.20.

4). Twardowski, O czynnościach i wytworach [On activities and creations], 4.20.

5). Stögbauer, O wyobrażeniach ogólnych [On general perceptions[O1] ], 2.10.

6). Helmholtz[O2] , Liczenie i mierzenie z punktu widzenia teoryi poznania [Counting and measuring from the point of view of the theory of cognition], 2.00.

———————

total 21.60 M.

On the assumption that the shipment will cost several marks, I’m paying a total of 26 M, to simplify the proceedings. In the event that this sum is insufficient, I’ll send the rest without delay.

The reason I’ve turned to Movement in the above matter is that I’ve tried more than once to buy these items in bookstores, but to no avail. They don’t have them in stock (as for Hume, I don’t know what the problem is!) and, in the case of the cheaper items, don’t want[O3] to bring them in. The problem of ordering books in Warsaw is very serious. I ordered, for example, a collected edition of Plato from Wende[O4] ’s in mid-January; so far, I haven’t received it. It was the same when I ordered Aristotle’s Metaphysics in November: after three months of waiting, I gave up. I’m currently bringing in books from Germany by writing to acquaintances who arrange this for me. Prices in our bookstores, meanwhile, are completely arbitrary. Recently, I was asked to pay 29 M for something (before the war it cost 7 M!), and when I protested and they proceeded to calculate it with me, it turned out to be only 17.60 M – and it was part of Gebethner[O5] ’s main stock! Accordingly, I prefer not to deal with Warsaw bookstores.

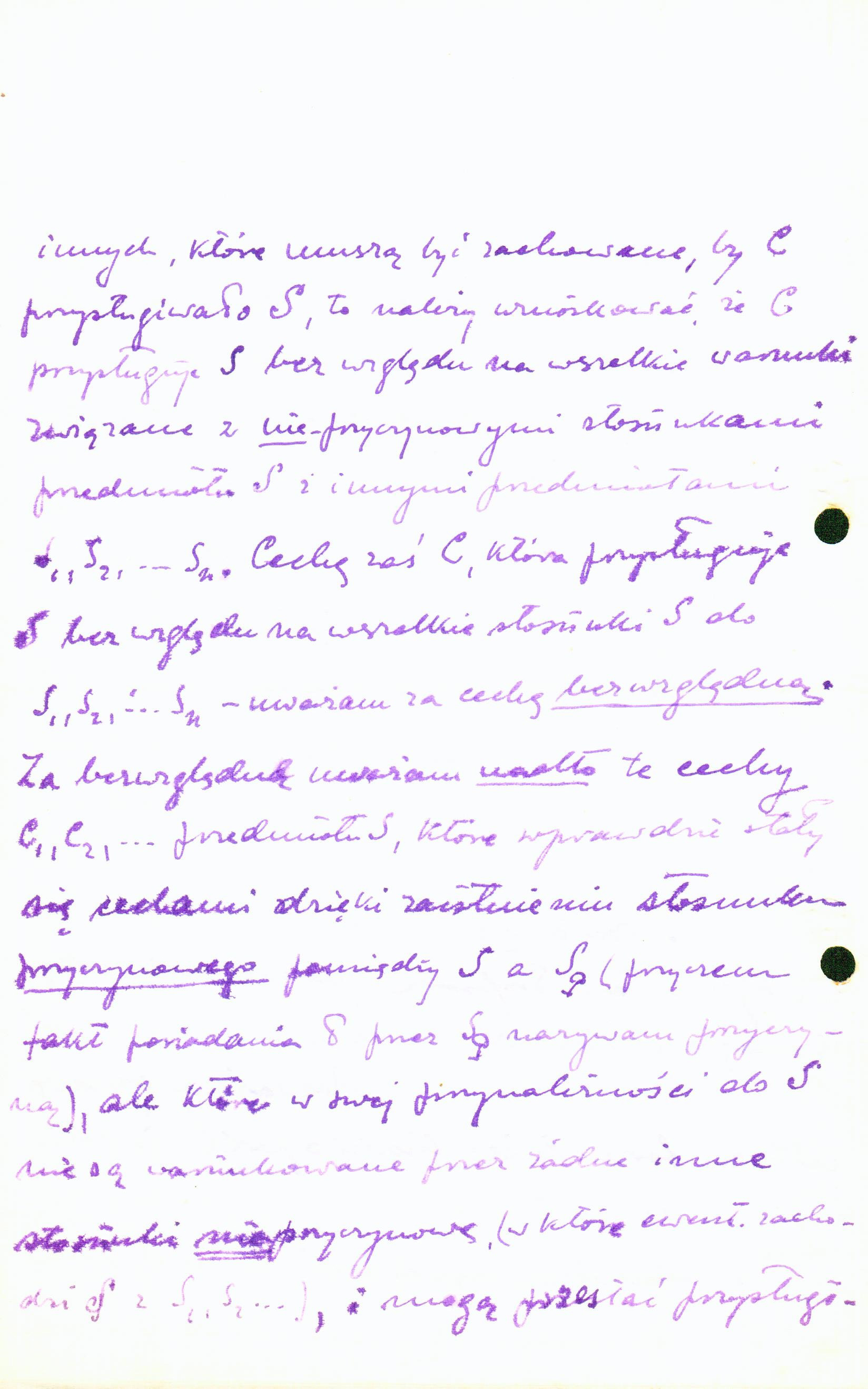

I’d like to finally explain why I was convinced that you consider the feature of clarity (or ambiguity) of a work as absolute. This is not stated literally in your article. Nevertheless, I believe that it was from this that I could have had the information required to assume such a position. Let us consider the matter quite formally: it’s a question of presenting a cause (C), feature (F), and subject (S). If the only condition for attributing F to S is C, and nothing is said about other conditions that must be met in order for F to be attributed to S, it must be concluded that F is attributable to S regardless of any conditions associated with non-causal relationships of the subject S with other subjects S1, S2, … Sn. I regard feature F, attributed to S regardless of any relationship of S to S1, S2, … Sn, as an absolute feature. Moreover, I consider the features F1, F2, … of subject S as absolute, as they have indeed become features thanks to the existence of a causal relationship between S and Sq (whereby I call the fact of Sq’s possession of F a cause) but, in their affiliation with S, they are not conditioned by any other non-causal relationships (in which S possibly derives from S1, S2 … ), and may cease to be attributable to S solely due to the emergence of new causal relationships between S and S1, S2, S3, which will cause their removal from the range of features of subject S.

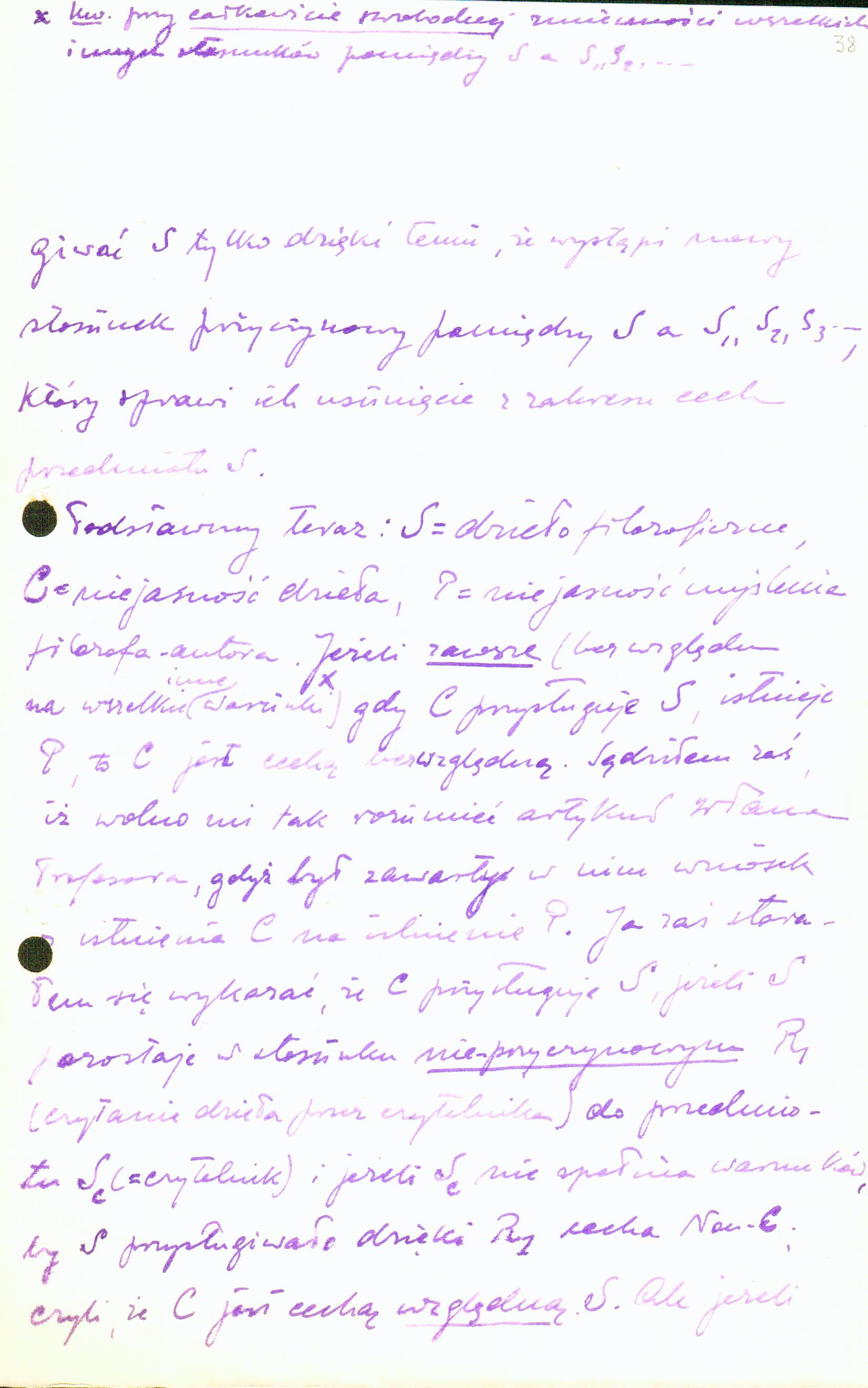

Now let us substitute: S = a philosophical paper, F = the paper’s ambiguity, C = the ambiguity of the philosopher-author’s thought. If it is always true (regardless of all other conditions) that F is attributable to S and C exists, then F is an absolute feature. I believed, then, that I might so understand your article, since it included a deduction, from the existence of F, of the existence of C. Meanwhile I tried to show that F is attributable to S, provided that S has a non-causal relationship R1 (the reading of the work by the reader) to the subject Sc (= the reader), and provided that Sc fails to fulfil the conditions for S to be attributed, thanks to R1, to feature non-F; that is, that F is a relative feature of S. But if this is so, it cannot be concluded, if F is attributable to S, that C exists, because F, in its attribution to S, is not conditioned solely by C.

In my article I tried to call attention to the conditions that must be met by the reader so that F is not attributed to S, under the assumption of clear thinking on the part of the philosopher-author. At the same time, I wished to emphasise that certain details of philosophical papers require particular aptitudes on the reader’s part in order to be clear. I was concerned with this because I’d very frequently encountered situations in which certain papers were regarded as ‘incomprehensible’ when they were merely ‘misunderstood’.

I am very happy that, regarding the ambiguity of a work being a relative feature, I am of the same opinion as you are. You might indeed accuse me of assuming in advance that you were incapable of holding a different opinion, since its legitimacy can be seen at a glance, and that you tacitly assumed that one can speak of the ambiguity of a work only in cases where the reader is completely qualified to understand it. But on the other hand, I was permitted to suppose that you had arguments to support the idea that ambiguity is not a relative feature – that, therefore, the article does not conceal near-obvious things but that a different approach to the matter is intended. And in that case the arguments were not only persuasive but enormously interesting. That was why I wrote that little article, in order to learn about those arguments.‒

Given this opportunity, I wanted to ask you whether Movement could use a review of Wölfflin[O6] ’s book entitled Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe [Principles of Art History]. Admittedly, this v. interesting book concerns first and foremost the history of art, but is equally interesting, I believe, to philosophers, particularly in the field of art.

Thanking you again for your kind letter and for kindly concerning yourself with the matter of my intended book purchases

I enclose expressions of profound esteem

Roman Ingarden

[O1]Może być też images, notions

[O2]Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-94)

[O3]oryg: chce, chyba chcą

[O4]założyciel: Edward Wende (1830-1914)

[O5]założyciel: Gustaw Adolf Gebethner (1831-1901)

[O6]Heinrich Wölfflin (1864‒1945)