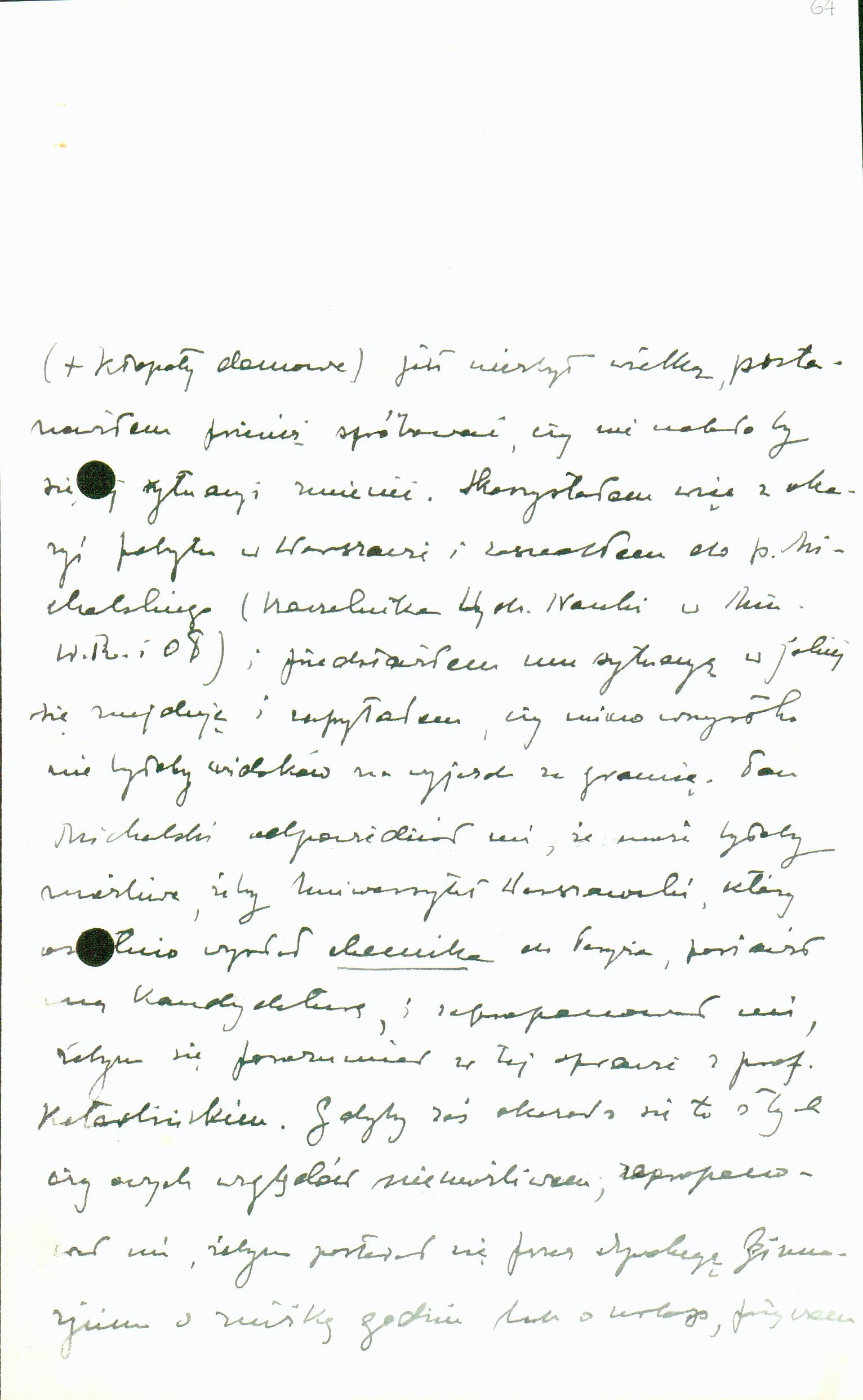

Letter to Kazimierz Twardowski written 28.03.1922

Toruń 28/3/1922

Most Honourable Professor!

At the moment I received your letter, I had a great number of assignments, as I was finishing an article on Max Scheler for Warsaw Review. Then I went to the TNSW [Towarzystwo Nauczycieli Szkół Wyższych; English: Society of Higher Education Teachers] Congress in Warsaw for a few days, as a delegate of the local District, and returned home only today.

Thus it’s only today that I’m able to fervently thank you for your latest letter of the 17th of this month, and especially for the position you’ve taken regarding the matter of my habilitation. This position again gave me a bit of hope of being able to devote my time wholly to original philosophical work, which, as you accurately state, I see as the essential task of my life. I’ll also do everything possible not to betray the trust you’ve placed in me, as manifested in the words of your latest letter. Meanwhile, the knowledge that the work I’ve done to date is not completely worthless will reinforce my strength in today’s so-difficult times.

As for the matter of the French scholarship, I fully understand your position and completely accept that the candidate who last year was forced to accept the fate of remaining in the country has not only a formal but also a moral right to priority over me. In view of the fact, however, that the prospect of fruitful original work in connection with 30 hours of work at school (+ domestic problems) is not very great, I decided at any rate to see whether it might not be possible to change this situation. Therefore I made use of my stay in Warsaw and went to see Mr Michalski [O1] (head of the Division of Science in the Min. WRiOP [Wyznań Religijnych i Oświecenia Publicznego; Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Education], presented to him the situation in which I find myself, and asked whether there might not be prospects of a trip abroad. Mr Michalski told me that perhaps it would be possible for the University of Warsaw, which recently sent a chemist to Paris, to put my candidacy forward, and asked me to communicate with Prof. Kotarbiński regarding this matter. If this turned out to be impossible for one reason or another, he suggested that I try to obtain a reduction of hours or leave of absence from the office of the headmaster of the middle school, in connection with which he expressed his readiness to grant me a ministerial scholarship at that time, which would enable me to do without the overtime compensation gained at school.

I intended to communicate with Prof. Kotarbiński; however, given that, before doing so, I learned that there is another candidate who is much (there can be absolutely no comparison) more deserving of the chance of a trip to Paris, and moreover an individual with whom I have a very close personal relationship, I decided to give up my efforts towards a French scholarship. Mr Michalski’s other suggestion ‒ provided no difficulties are encountered on the part of the school ‒ will give me (I hope) the opportunity to write my habilitation thesis and prepare myself for the colloquium. Of course, the reduction of my hours or leave can come into play only as of the beginning of the next school year. However, since the period of hardest work this year has already passed, and later the holidays, I hope that by September I’ll achieve such results that a half-year’s leave would enable me to complete my habilitation thesis.

Of course, a great deal depends on the choice of the topic of the thesis ‒ and I’m also very grateful to you for suggesting that we should come to an agreement on this matter. Well, first of all, I’d like to lay out some general indications, and then outline the topic in a few short lines and ask if it would be suitable, in your opinion, for a habilitation thesis.

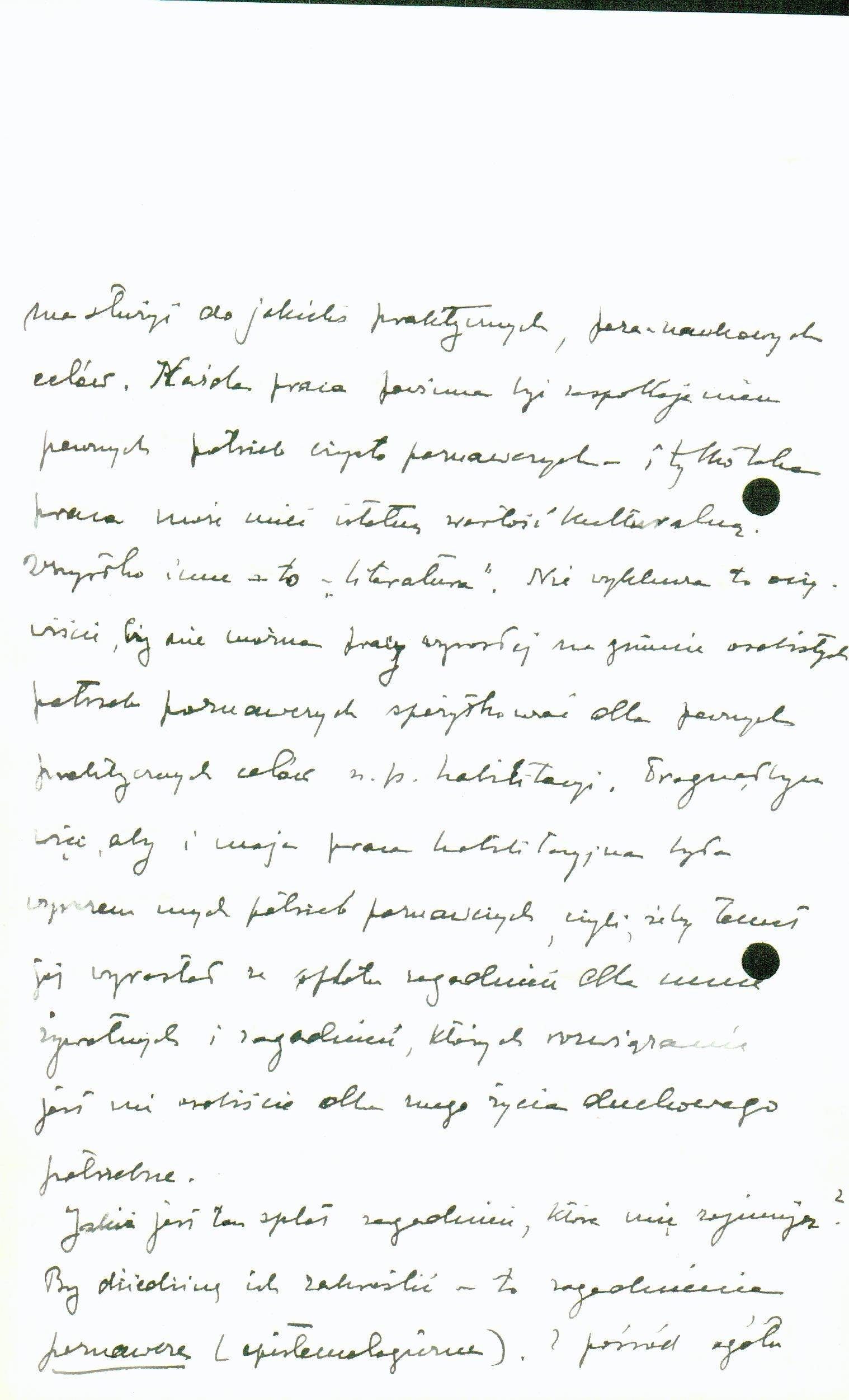

Well, then, I believe one should never write any academic ‒ especially philosophical ‒ paper in order to serve practical, non-academic purposes. Each paper should represent the satisfaction of certain purely cognitive needs ‒ and only such a paper is capable of possessing essential cultural value. Everything else is ‘literature’. This, of course, does not exclude the use of a paper that has evolved based on personal cognitive needs for certain practical purposes, e.g. habilitation. Therefore, I’d want my habilitation thesis to be an expression of my cognitive needs, that is, for its topic to evolve from a plexus of issues which are vital for me and whose solutions are necessary to me personally for the sake of my spiritual needs.

Of what sort is this plexus of issues that occupy me? To circumscribe the relevant field: these are cognitive (epistemological) issues. Generally, among cognitive issues: the essence and value of cognition of the real external world, along with its metaphysical consequences (‘idealism’, ‘realism’, and so on). Among these, the central and most important modern problem, beginning with Hume, has been the theory of cognition: the ‘objective’ problem, or, if one may so put it, the ‘metaphysical’ validity of what Kant called ‘categories’, what e.g. in Bergson are called ‘schemata of intellectual cognition’. In other words, specifically: whether sensual cognition (external perception), which presents the world to us as a set of self-contained (in relation to each other) elements (substances) in causal relations, truly has a formal categorical relationship to the construction of the real external world or not. This question, moreover, applies equally well to the picture of the world supplied to us by external observation as to the picture of the world towards which physics has been recently heading. In categorical terms, there is no essential difference here – after all, the atomistic view is (figuratively speaking) a microscopic projection of the picture of the world perceived visually.

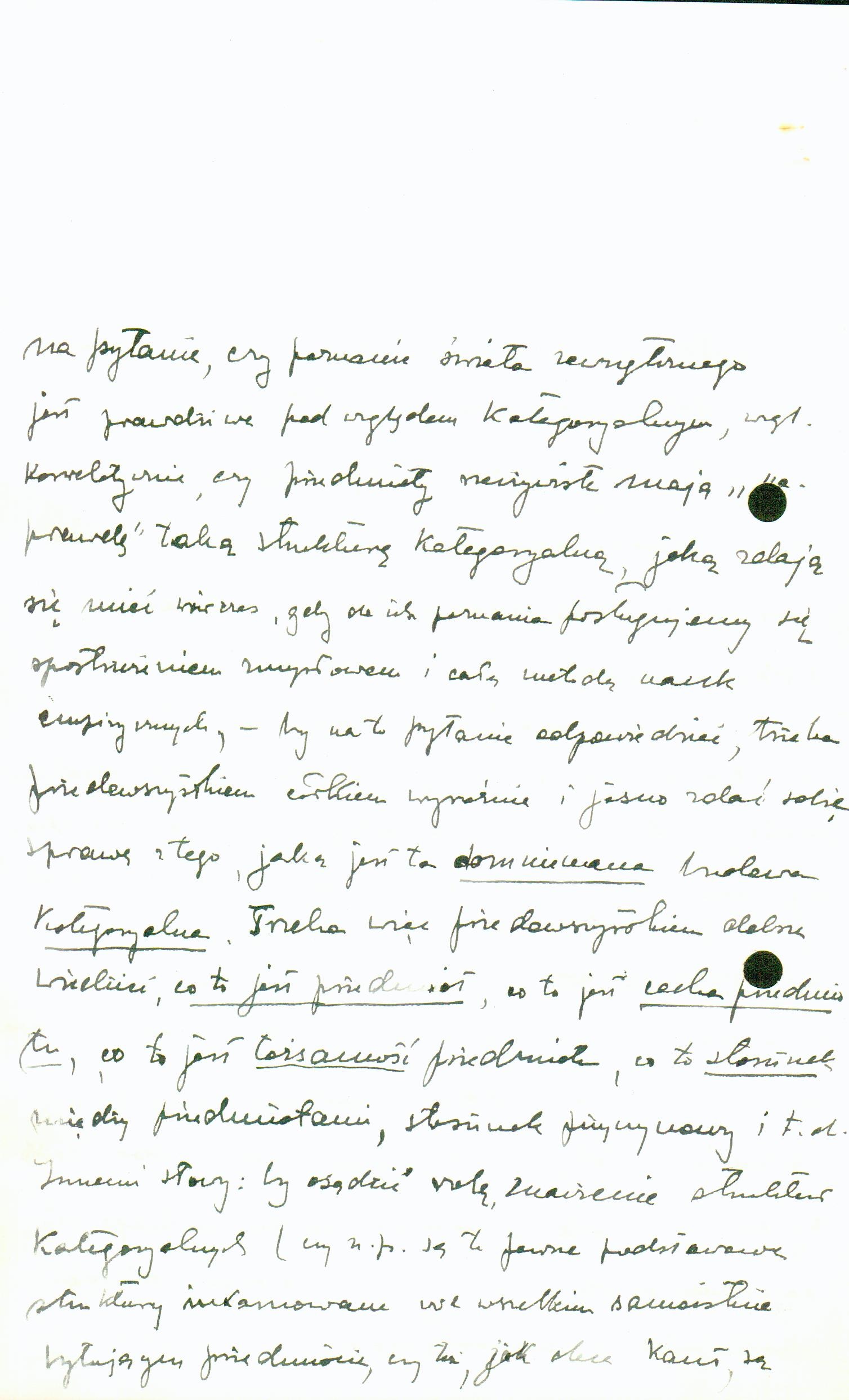

The problem of the metaphysical validity of the categorical system had already outlined itself for me very clearly when I was working on Bergson, and everything that I’ve been thinking and working on since then has gone towards solving this problem. It’s also one of the central questions of [Husserl’s] Ideen zu einer reinen Phaenomenologie [Phänomenologie] [Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology] – to the point that its solution, beyond its vital significance, enables one to occupy ultimate positions not only in terms of Bergsonism, but also in terms of the so-called ‘idealism of Husserl’ and of Kantism. I suppose, then, that if it were possible to shed light on the darkness surrounding this problem, this would represent an important step forward in the field of the theory of cognition ‒ and, yes, in metaphysics. But to be able to approach this issue, a whole range of issues which, at first glance, are seemingly loosely related to the issue at hand (which, of course, I’ve sketched here only in the most general terms) must first be developed. These questions are grouped, on one hand, in a series of methodological issues (one detail of which is e.g. the issue of the paper of which I published Chapter I in Volume IV of [Phenomenological] Yearbook, entitled ‘Ueber [Über] die Gefahr einer petitio principii in der Erkenntnistheorie’ [German: On the danger of a petitio principii in epistemology]; others are sketched in chapters I and II of a critical part of my paper on Bergson, which has already been published); on the other hand, in a plexus of issues in the field of formal ontology (in Husserl’s sense). The bridge leading from the above-mentioned central issue to related ontological issues can be briefly summarised as follows: In order to be able to answer the question of whether cognition of the external world is true in categorical, or correlative, terms, whether real objects ‘truly’ possess such a categorical structure as they seem to possess when we use sensory perception and the whole method of empirical science to recognise them ‒ to answer this question, it is necessary above all to quite clearly grasp the nature of this alleged categorical structure. Thus, first and foremost, it is necessary to know what an object is, its features, its identity, the relationship between objects, causality, and so on. In other words: to evaluate the role and significance of categorical structures (whether e.g. certain basic structures are incarnated in any self-contained object, or whether, as Kant would have it, these are only subjective forms imposed on a reality which is foreign to them, and so on). One must first recognise, if I may so express it, the content of these structures (what qualitas is, what substance is, what is encompassed by the meaning of substance, attribute, relationship, conjuncture, and so on).

I don’t know if these few sentences can explain what I mean in this case. If not, please kindly inform me and I’ll try to be clearer.

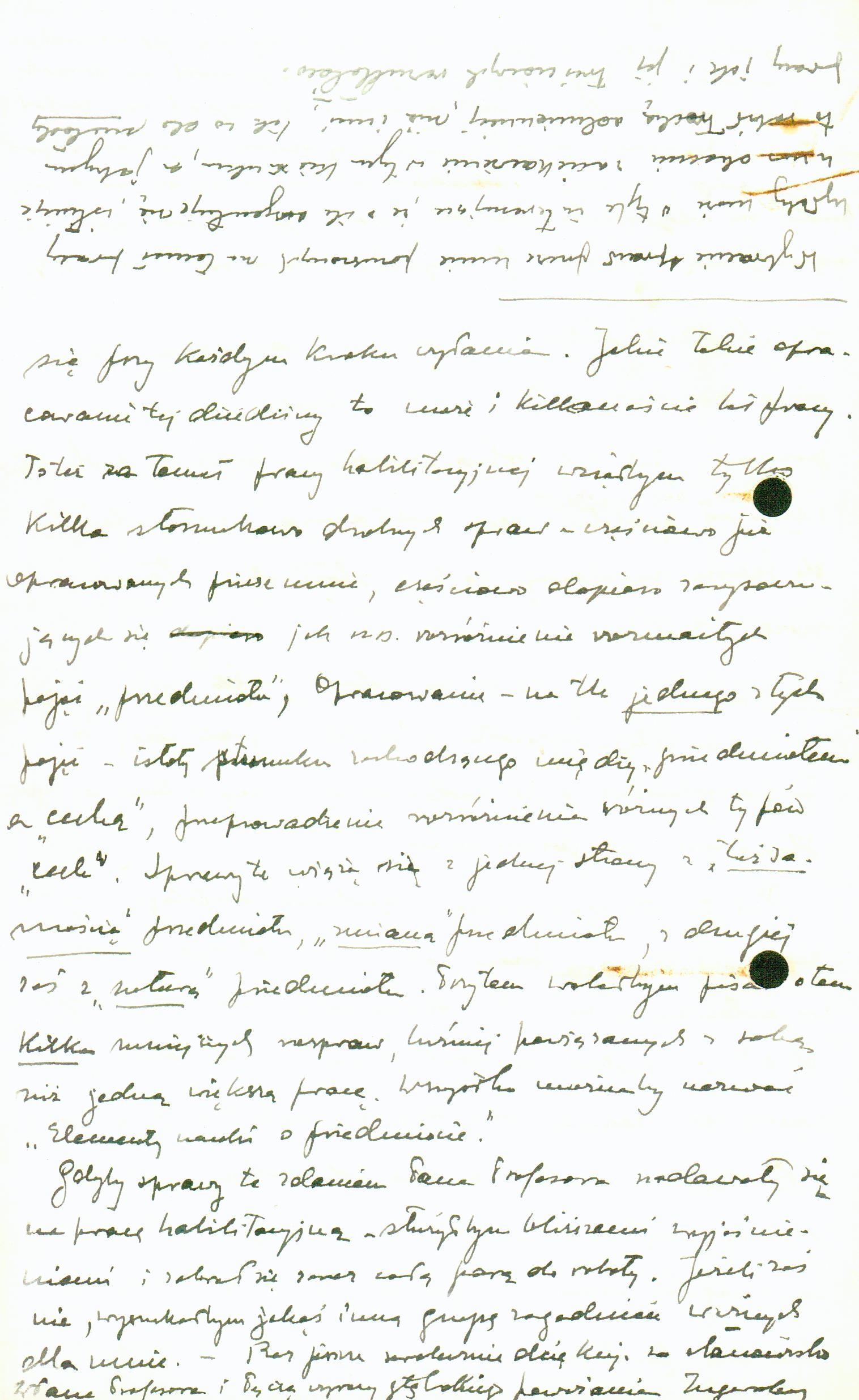

Well, this other group of ontological issues is occupying me for the third year now. Without orienting myself one way or another on these matters, I can go no further with the central issue. Well, then, if it were possible to write something in this field as a habilitation dissertation, I would be very happy, because that way I wouldn’t have to abandon the path marked out for several years of work. ‒ Admittedly, these issues are very difficult and complicated. In addition, a great number of issues emerge at every step. One way or another, development of this field may mean between ten and twenty years of work. Therefore, for the habilitation thesis, I would take up only a few relatively small matters ‒ which I have, in part, already developed, and which in part are outlining themselves only now, such as the distinction between various concepts of the ‘object’, the development ‒ against the background of one of these concepts ‒ the essence of the relationship between the ‘object’ and the ‘attribute’, the differentiation of various types of ‘attribute’. These matters are associated on one hand with the ‘identity’, on the other with the ‘nature’, of the object. Accordingly, I’d prefer to write several shorter, loosely related dissertations, as opposed to one larger paper. The whole thing might be called ‘Elements of learning about an object’.

If these issues, in your opinion, are appropriate for a habilitation thesis, I’ll provide more exact explanations and immediately get to work at full steam. If not, I’ll look for some other group of issues that are important to me. ‒ Thank you once again for the position you’ve taken, and I enclose expressions of profound esteem

Ingarden

[O1]Stanisław Michalski (1865‒1949)